Should Kratom be banned?

Recently the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a public statement concerning the “deadly risks” associated with the ingestion of a herb commonly referred to as kratom, also referred to as ketum, biak-biak, kakuam, ithang, or thom. This follows a response by law-makers in some US States that have out-right banned the use of kratom, and an intention by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) in 2016 to place kratom into Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. North of the border in Canada, kratom is allowed for sale but has not been approved for use by Health Canada, and thus like in other US states where it isn’t banned, it is being sold euphemistically as “incense powder” or some other non-helpful product description to skirt its quasi-legal status. Clearly there are some regulatory issues here that need to be resolved, but what are we to make of the FDA’s claim that kratom is “deadly”?

What is Kratom?

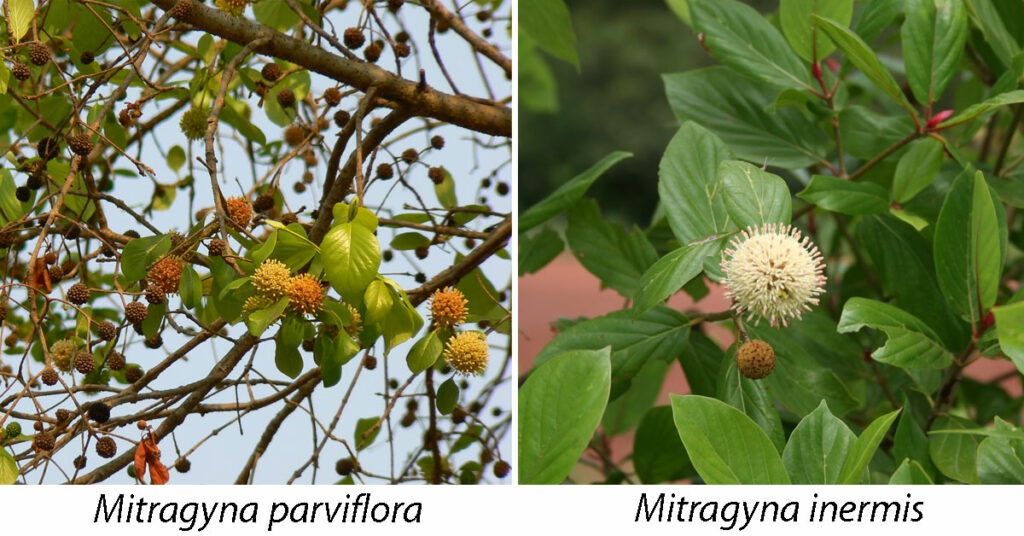

Pronounced “kra-TOM” in the Thai language, kratom is one among several species of deciduous to evergreen trees contained within the Mitragyna genus, related to the coffee bean (Rubiaceae), naturally distributed throughout South East Asia as well as Africa. Besides kratom, several Mitragyna species are used therapeutically in traditional medicine. In Ayurveda this includes the herb vitānaḥ (Mitragyna parviflora), the leaves used as an anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, and analgesic herb to balance vāta and kapha doṣa (Warrier et al 1994). In the tropical regions of Africa the leaves of Mitragyna inermis, known as “giyayya” by the Hausa people of Nigeria, are used as a traditional medicine to treat several disorders including diabetes, rheumatism, malaria, skin disease, jaundice, and epilepsy (Konkon et al. 2008,von Maydell H 1990).

Kratom specifically refers to Mitragyna speciosa, an evergreen tree with greyish bark and glossy green leaves with a globe-shaped inflorescence comprised of small yellow flowers. The native habitat of kratom includes Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea, and in some of these regions, kratom is cultivated for domestic use, and more recently for the export market, providing an important source of new income for local farmers. There are also related species such as Mitragyna hirsuta and Mitragyna javanica that appear to share some of the same medicinal properties as kratom.

There are a number of commercial “strains” of kratom leaf, often identified by the color of the leaf venation (e.g. “red,” “green,” “white,” or “yellow”), and the location of where it’s grown (e.g. “Borneo,” “Ketapang,” “Thai” etc.). As the plant grows and produces leaves the color of the leaf venation changes with age. In some specimens the young leaves begin with reddish colored veins, but as the leaf matures the veins turn green, and then become paler and more yellowed with age.

History and traditional use of Kratom

Like many of the other Mitragyna species, kratom has a long history of use in SE Asia, both as a food and a medicinal herb. Among the earliest published ethnobotanical reports on kratom was a treatise authored by Burkill and Haniff in 1930, describing some of the key uses for kratom among the Malay villagers they studied: as a wound-healer; as a vermifuge to kill parasites; in the treatment of splenomegaly; and as a treatment for opiate addiction. While other traditional uses for kratom have been described elsewhere, including the treatment of fever, cough, gastritis, diarrhea, kidney pain, and broken bones, it’s the ability of kratom to treat opiate addiction that has garnered the most attention – particularly from public health authorities such as the FDA. Anything that has the ability to treat opiate addiction and pain at the same time, a seemingly reasoned argument begins, must itself be a powerful drug and therefore unsafe. If the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) proceeds and places kratom into Schedule I, it not only becomes illegal from Americans to consume kratom for personal use, it no longer has any kind of acceptable medical use, hampering further research into its traditional benefits: including the treatment of opiate addiction. Although there is broad acceptance that the US is struggling with an opioid epidemic, consuming more than 80% of the world’s opioid supply, these drugs make a lot of money. The wealthy American family that owns Purdue Pharma, which manufactures oxycontin, has a net worth of over $13 billion, and as history shows, this kind of concentration in wealth and power has a profound ability to unduly influence public health policy.

Apart from its medicinal uses, kratom has long been consumed by farm workers in SE Asia as a way to enhance mood and improve productivity, in much the same way as coffee and tea are consumed elsewhere in the world. A policy statement on kratom issued by the DEA (download link) refers to the fact that Thailand banned kratom in 1943, but it doesn’t indicate the reasons why. Spilling over from the Anglo-Chinese Opium Wars of the mid-19th century, opium addiction had become a widespread phenomena throughout Asia, including Thailand, and by the early 20th century the Thai government was relying on state taxes derived from opium production. Poor farm workers that had become addicted to opium but couldn’t afford their habit turned to traditional healers, who introduced them to the use of kratom. In a relatively short period of time the use of kratom to prevent and treat opiate addiction became widespread knowledge, and government revenues began to take a huge hit as opium consumption began to decline. Thus, in response to this economic threat, the Thai government banned the production, sale, and use of kratom, and in 1979, formally classified it as a narcotic drug.

While this ban in Thailand did have some impact on the sale and trade of kratom, as far as personal use it was largely ignored, as kratom is naturally abundant and so widely used that any kind of ban was impossible to enforce. This doesn’t mean that the Thai government didn’t try to stop the use of kratom, but in the end its efforts hardly had any impact, as today it is estimated that upwards of 70% of male Thai villagers in some districts consume kratom on a regular basis (Tanguay 2011). Although this kind of use appears to parallel the opioid epidemic in the US, recent studies investigating the social functioning of regular kratom users in Thailand have found that unlike drugs such as oxycontin, the regular use of kratom results in no significant impacts or impairments. As a result, there is a general consensus among community leaders, academics and policymakers in Thailand, as well as public health and law enforcement officials, that “kratom use and dependence carry little, if any, health risks”(Brown et al 2017). In contrast, the FDA attributes at least 36 recently reported deaths to kratom ingestion, despite the fact that in every one of these cases users were also consuming alcohol, illicit substances, and/or prescription drugs, all of which have well-established health risks. Thus, to attribute kratom as the cause of these deaths, particularly in light of the experience in SE Asia, is not only premature and myopic, but demonstrates a clear bias.

Phytochemical attributes of kratom

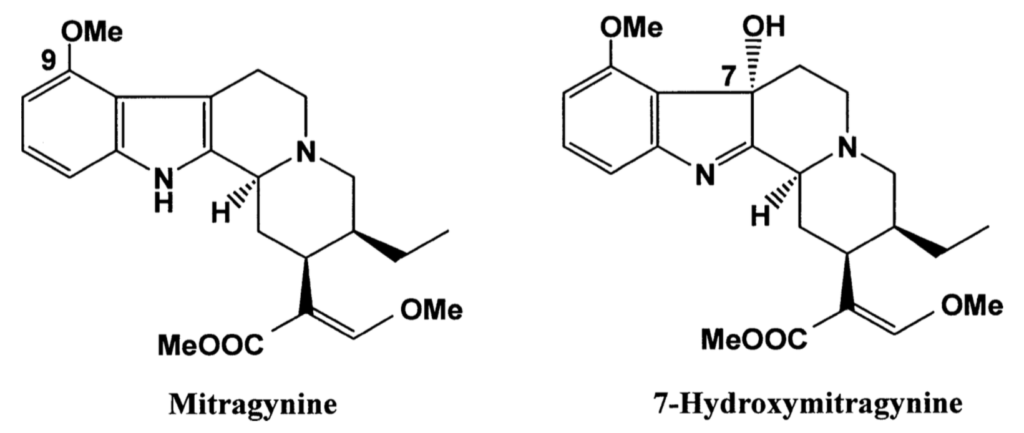

Kratom has some interesting phytochemical attributes, including a range of compounds such as flavonoids, triterpenoids, and secoirioids. Research has demonstrated that these compounds possess broad pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antitumor, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, and anticonvulsant properties (Gong et al). Of primary interest to researchers, however, are a mixture of indole and oxindole alkaloids found within kratom leaf, comprising up to 1.5% of the total phytochemical content. Two alkaloids called mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine have attracted the most interest, considered to be responsible for the psychotropic effects attributed to kratom. Mitragynine is by far the most abundant of the two, comprising between 12-66% of the total alkaloid content, depending on where the herb is sourced (e.g. lower levels in Malaysia versus higher levels in Thailand), and its stage of maturity during harvest. In contrast, 7-hydroxymitragynine is an oxidized form (congener) of mitragynine that comprises less than 2% of kratom’s total alkaloid content, although these levels can be increased modestly by exposing the freshly dried leaf to the sun (giving rising to “yellow” or“gold” strains of kratom) (Kruegel et al 2016).

Both mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine are opioid receptor agonists, similar in effect but chemically different from conventional opioids such as morphine and oxycodone. In this way, kratom has a similar but much weaker analgesic property than conventional opioids. The effect of opioid-agonists is in part related to the specific receptor sub-type they interact with, including delta (δ), kappa (κ), and mu (μ) opioid receptors. Of these three, conventional opioid drugs such as oxycodone primarily target the μ-opioid receptor, which apart from producing an analgesic effect, also promotes respiratory depression, which is a major cause of death from overdose.

Mitragynine exerts the highest affinity for κ-opioid receptors, followed by μ- and δ-opioid receptors, whereas 7-hydroxymitragynine targets primarily the μ-opioid receptor (Suhaimi et al). Compared to morphine mitragynine is only about 26% as potent, whereas 7-hydroxymitragynine is about 10 times more potent than morphine (Takayama et al). With regard to the whole plant, however, kratom has been shown to have 350 times less affinity for the opioid receptor than morphine (Hassan et al 2013), underscoring a clear difference between the isolated alkaloids and the crude herb.

Another important difference between the most potent opioids in kratom, i.e. 7-hydroxymitragynine and its derivatives, is that it by-passes the activity of β-arrestin-2, an intracellular protein that interacts with receptors and signaling pathways to mediate the behavioral effects of opioid drugs. By failing to recruit β-arrestin-2, 7-hydroxymitragynine appears to slow the development of tolerance and physical dependence, demonstrating a dramatic reduction in unwanted side-effects such as respiratory depression and constipation (Váradi et al 2016).

While the presence of mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine in kratom explains its opiate like effects in higher doses, it has been observed that in smaller doses, kratom has stimulatory effects. While this effect isn’t completely understood, it has been shown that the chemical structure of mitragynine incorporates the nucleus of tryptamine, and interacts with serotonergic and adrenergic systems to provide a stimulating, mood-enhancing effect (Adkins et al 2011).

Kratom, opiates, and pain

As a herbalist I must admit that I am a little late to the game when it comes to kratom. While it was on my radar, I simply didn’t pay much attention to it, mostly because I was aware of its potential for “abuse” as a “legal high.” Besides which, if I need to use a herb with analgesic properties, I already have several herbs at my disposal, including yanhusuo (Corydalis yanhusuo), blue poppy (Meconopsis spp.), kava (Piper methysticum), Jamaican dogwood (Piscidia erythrina), and willow (Salix spp.). But as any physician should know, simply treating pain alone does not resolve the issue. Pain serves a vital function, letting us know when something is wrong. The only correct use of an analgesic is if measures have been undertaken to remove the cause of injury and promote healing. This is why when treating chronic pain I often insist upon dietary changes to resolve gut dysfunction – an important contributor to chronic inflammation – as well as use herbs and formulas both topically and internally that aren’t necessarily analgesic, but nonetheless promote healing and resolution. Thus, relying upon kratom in the treatment of chronic pain without also addressing causative factors is a kind of misuse of this herb. Remember – pain tells us that something is wrong – we need pain in order to function correctly. It is a desire to experience a lack of pain, and to root out its causes, that brings us to a healthier state.

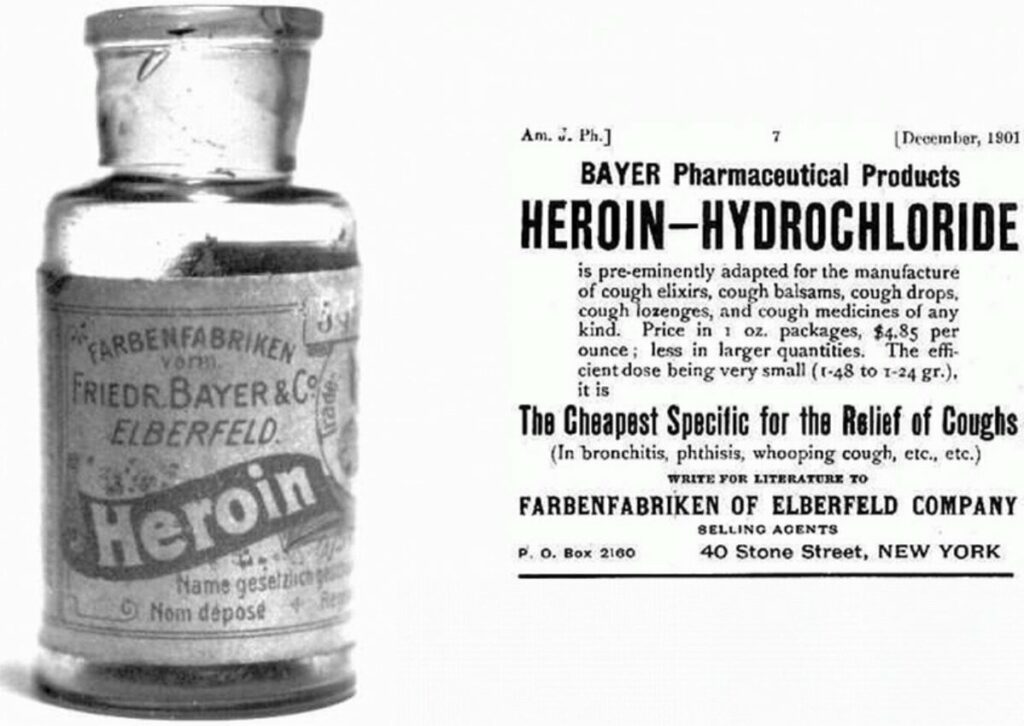

In North America, the opioid epidemic originated with the free use of morphine during the American Civil War, creating a huge underclass of morphine-addicted soldiers that were both physically and emotionally traumatized by the brutality of their experiences. In 1895 the German pharmaceutical company Bayer began to market a highly effective treatment for morphine addiction called “heroin,” and soon morphine addicts became heroin addicts, and ever since, opiate addiction has been a chronic problem in North American society. Although heroin was no longer available as an OTC drug by 1914, pharmaceutical companies continued to conduct research into the development of even more powerful opioids. Understanding the vast untapped market potential of these drugs, pharmaceutical companies hired physicians to promote a libertine approach to prescribing opioids, even for relatively minor issues, suggesting that any kind of pain must be treated aggressively. Although this suggestion was seemingly cloaked by empathy and compassion, in reality, it was a corporate take-over of the medical field, where generations of physicians were duped into thinking they were doing good by handing out powerful opioids like candy.

But apart from the greed of the pharmaceutical companies, and the willful ignorance of doctors who followed the dictates of their profession, much of the blame lies with consumers. Although pain is a physical sensation, it is also an emotional response. Consider Tibetan Buddhist monks practicing “tummo” meditation in frigid conditions, or an athlete able to perform great feats despite physical pain. When we control our emotions we are in charge of our minds, and through mental control we can actually change the way we experience pain. The only way to realize this, however, is to not take for granted the permanence of materiality. It requires us to understand that the mind essentially creates our reality, and that within certain limitations, we can change the very nature of our being by changing our minds. This underscores the importance of studying the mind, and the cultivation of self-understanding. This notion of self-reflection, however, is in large part the antithesis of American culture, whether expressed in the crass materialism of its political and religious leaders, or as is the case in science and technology, failing to account for the impact of innovation, whether it’s plastic pollution or the development of powerful opioid drugs. In other words, the opioid epidemic exists in North America because its victims have little understanding of their own minds. Users are caught in a loop of suffering and pain, and without the required effort to transcend this state, taking kratom could be nothing more than substituting one problem for another.

Therapeutic uses for Kratom

In many respects kratom is a remarkable herb, and has a number of therapeutic uses that are different depending on the dosage used. As the experience in SE Asia has shown, kratom is an exceptionally useful herb to help wean patients off of illicit and legally prescribed opiates. Given that kratom lacks many of the side-effects of conventional opioids, using it as a substitute can be a definite improvement, but if supportive measures to address the causes of addiction aren’t put in place, then kratom can become an addictive substance. If you are struggling with addiction, please understand that simply taking kratom is not a sustainable solution.

Another important use for kratom is in the treatment of pain. To achieve this effect relatively large doses of the powdered leaf need to be ingested, between 5-10 grams, mixed with water or juice, taken up to 2-3 times daily. The effects of kratom are generally noticed within 20 minutes of consumption, and last between 3-5 hours. These kind of doses, however, are not without problematic side-effects, including nausea, itching, sweating, and a dry mouth. It is generally better to take small doses of kratom initially, between 1-2 grams or less, and gradually work your way up to an effective dose. There is also some research suggesting that taking large amounts may cause liver problems (Kapp et al 2011), and hence, using kratom in higher doses should only be undertaken for a limited duration. Large doses are also more likely to cause problems such as constipation, and if such side effects are experienced, the dose should be reduced accordingly. For constipation, herbs can be taken to help to support the liver and bowels, such as gudūcī vine (Tinospora cordifolia) and Triphalā cūrṇa. When taking kratom in larger doses, like conventional opioids, there is still some risk of physical dependency, and when weaning off of such doses, users may experience withdrawal symptoms such as flu-like symptoms, sweating, nausea, restlessness, anxiety, and insomnia. While these symptoms are usually nowhere near as difficult as conventional opioids, they are significant enough that some users may have a hard time getting off of kratom.

Earlier reference was made to the fact that in smaller doses kratom has stimulatory properties. The effect can be described as similar to but milder than other psychostimulants such as cocaine and amphetamine, without side-effects such as hyperactivity, muscle spasm, and jaw clenching. Smaller doses between 1-3 grams of the powdered leaf, taken up to 2-3 times daily, can promote a sensation of increased sociability, ease, and contentment, and can be highly effective as part of a treatment plan for depression and anxiety. In my practice, I have seen how kratom can be used in place of amphetamines such as ritalin and dexedrine in the treatment of attention deficit disorder, but without the side-effects that mar the use of these drugs.

Another potential use for kratom is the treatment of insomnia, particularly if the cause of insomnia is physical pain. For this purpose larger doses of between 5-10 grams can be helpful, but because kratom also has stimulatory effects it can actually make insomnia worse. For many people, insomnia is caused by stress and over-thinking, and it is too much to expect of any medication that a single dose before bed can compensate for an entire day of disordered brain function. When I treat insomnia, I place a big emphasis on managing stress and engaging in lifestyle activities that promote healthy brain balance, such as spending time in nature, creative expression, and meditation. In many cases it is better to take small doses of kratom during the day to promote mental balance, along with herbs such as brahmi (Bacopa monnieri) and reishi mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum), and then take GABA-ergic herbs such as aśvagandhā root (Withania somnifera) or lime blossom (Tilia cordata) in the evening to gently inhibit excitatory neural pathways in the brain, promoting a restful sleep.

The different types of kratom

Similar to the way cannabis dispensaries draw deep distinctions between different strains of marijuana, kratom merchants also like to emphasize differences between their commercial strains. But while the differences in cannabis strains can be objectively determined based on the presence of different cannabinoids, such as THC (tetrahydrocannabinol), CBD (cannabidiol), and CBN (cannabinol), we are still lacking sufficient phytochemical knowledge on kratom to understand how the color of leaf venation, the ecotype where it’s grown, the maturity of the leaf prior to harvest, and other factors such as oxidation or exposure to sunlight, play a role in the effects of kratom.

Like all strains of cannabis that contain THC, all kratom is essentially the same, but there are some nuanced differences. Generally speaking, leaves with red venation tend to have more sedative, pain-relieving effects; “white” strains tend to have more stimulatory effects; and the “green” strains are somewhere in between. “Yellow” and “gold” strains of kratom have been oxidized by sunlight and/or fermented during drying, and may have higher levels of 7-hydroxymitragynine, and thus more of a sedative effect. Because of the complex phytochemistry involved, however, as well as the uniqueness of each individual, how one person responds to one strain may be very different from another. If you want to experiment with kratom, it is recommended that you try out a few different strains and determine for yourself what works best for you, and always start at a low dose, i.e. between 1-2 grams, or less.

One particular kratom product I would urge you to avoid, however, are the so-called “super” strains as well as concentrated extracts (i.e.“tinctures”). Crude kratom leaf is powerful enough to do the job, and taking such products increases the likelihood of side-effects and withdrawal problems, and should be assiduously avoided. Likewise, it is very important to acquire kratom from a reputable vendor, which given the current regulatory issues, can be something of a challenge. While I do not endorse any particular merchant, you can review the comments and opinions on discussion-based websites such as reddit, where users share and compare their personal experiences.

Should kratom be banned?

Of course not! But that’s my opinion for all herbs, including cannabis, and for any substance ingested or otherwise applied for personal use. We are all creatures born from this earth, living off of what she provides for free. In this way, we are all inherently born free: any other understanding is just a human construct. The relationship each of us has with our bodies is sacrosanct, and in well-reasoned, healthy adults, we have the inherent right to do whatever each of us wants to do with them. As the experience in Thailand has shown, simply banning kratom does little good, and like other illicit drugs found in North America, it creates a black market controlled by criminal enterprise that has far worse outcomes than allowing the legalization of kratom.

This does not mean that I think kratom is inherently safe. Water is essential for life, and yet it is still possible to drown in water. A cup or two of coffee is innocuous enough, but if you’re drinking 10 cups of coffee on a daily basis, it’s very likely you’re experiencing a host of other health issues, such headaches, digestive problems, and back pain. We would all be better off if we admitted that life isn’t possible without causing some degree of harm. We have to accept this harm but also try to learn from it. Being the intelligent creatures we are, we can communicate our experiences with these substances to others, and examine what the scientific research tells us. Based on my research as well as personal and clinical experience, if we understand its potential for abuse and use it with due care and caution, kratom can be an exceptionally useful herb for a number of the common maladies that afflict modern life.

References

Adkins JE, Boyer EW, McCurdy CR. 2011. Mitragyna speciosa, a psychoactive tree from Southeast Asia with opioid activity. Curr Top Med Chem.11(9):1165-75.

Brown PN, Lund JA, Murch SJ. 2017. A botanical, phytochemical and ethnomedicinal review of the genus Mitragyna korth: Implications for products sold as kratom. J Ethnopharmacol. 202:302-325.

Burkill I. H., Haniff M. 1930. Malay village medicine. The Garden’s Bulletin Straits Settlement. 6:165–207.

Gong F, Gu HP, Xu, Q, Kang W. 2012. Genus Mitragyna: Ethnomedicinal uses and pharmacological studies. Phytopharmacology. 3(2) 263-272

Hassan Z, Muzaimi M, Navaratnam V et al. 2013. From Kratom to mitragynine and its derivatives: physiological and behavioural effects related to use, abuse, and addiction.Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 37(2):138-51.

Kapp FG, Maurer HH, Auwärter V, Winkelmann M, Hermanns-Clausen M. 2011. Intrahepatic cholestasis following abuse of powdered kratom (Mitragyna speciosa). J Med Toxicol. 7(3):227-31.

Konkon NG et al. 2008 Toxicological and phytochemical screening study of Mitragyna Inermis (Willd.) O ktze (Rubiaceae), anti-diabetic plant. J. Med. Plants Res. 2:279–284.

Kruegel AC, Gassaway MM, Kapoor A et al. 2016. Synthetic and Receptor Signaling Explorations of the Mitragyna Alkaloids: Mitragynine as an Atypical Molecular Framework for Opioid Receptor Modulators. J Am Chem Soc. 1;138(21):6754-64

Suhaimi FW, Yusoff NH, Hassan R, et al.2016. Neurobiology of Kratom and its main alkaloid mitragynine. Brain Res Bull. 126(Pt 1):29-40.

Takayama H, Ishikawa H, Kurihara M, et al. 2002. Studies on the synthesis and opioid agonistic activities of mitragynine-related indole alkaloids: discovery of opioid agonists structurally different from other opioid ligands. J Med Chem. 25;45(9):1949-56.

Tanguay, P. 2011. Kratom in Thailand: Decriminalisation and Community Control? In: Series on Legislative Reform of Drug Policies. Transnational Institute. Nr. 13

Váradi A, Marrone GF, Palmer TC, et al. 2016. Mitragynine/Corynantheidine Pseudoindoxyls As Opioid Analgesics with Mu Agonism and Delta Antagonism, Which Do Not Recruit β-Arrestin-2. J Med Chem. 22;59(18):8381-97.

von Maydell H 1990. Trees and Shrubs of the Sahel. Their Characteristics and Uses. Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit, Germany p 774

Warrier PK et al. (eds) 1994. Indian Medicinal Plants: A compendium of 500 species, vol 4. Orient Longman, Hyderabad p 45

Great review!