Vegetarianism and Ayurveda

In my blog last week, I addressed the mistaken belief held by some in the Āyurveda community that sufficient vitamin B12 can be obtained from plant-based foods. Unfortunately, this misperception is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the all-pervading belief both within and without the community of Āyurveda, that it is (primarily) a vegetarian-based system. Considering the decades of knowledge that we have accumulated on the very real issue of vitamin B12 deficiency, the notion that vitamin B12 can be obtained in plant foods is really nothing more than wishful-thinking, typically expressed by those who believe that eating meat is morally wrong. Normally, what someone personally believes isn’t my concern, but when this belief obscures the practice of Āyurveda, denies the basic science, and puts the public health at risk, it is important to speak out.

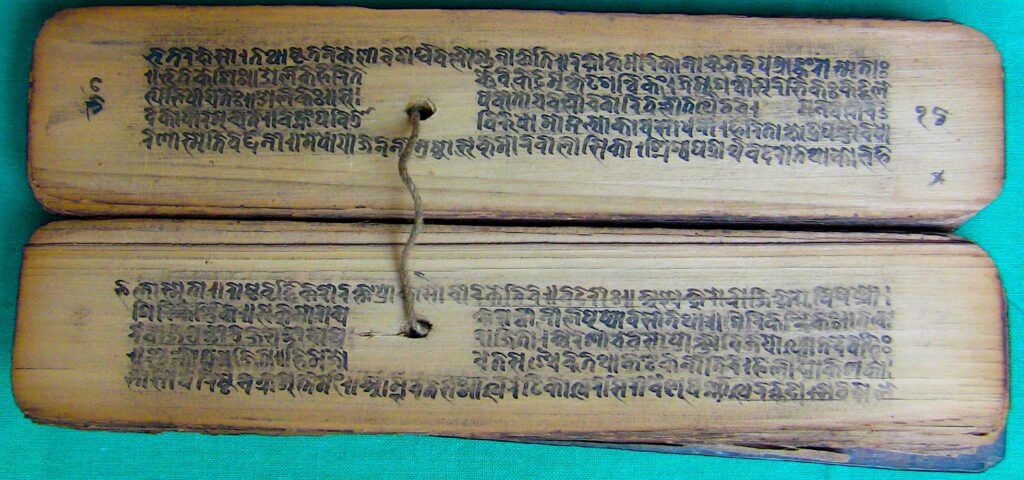

As painful as it may be for some to hear, the very real truth is that Āyurveda is not, and never was, a vegetarian system. There is nothing in any classical text of Āyurveda, including those of the bṛhat trayī (Caraka, Suśruta, Vāgbhaṭa) or the laghu trayī (Mādhava, Śāraṅgadhara, Bhāvaprakāśa), to suggest otherwise. All of these texts and many others not mentioned fully describe the qualities and properties of a multitude of animal products, including their use in the treatment of disease. With regard to the latter, out of the many diseases and syndromes described by Āyurveda, only for the disease of unmāda (psychosis) is a vegetarian diet sometimes prescribed, but not consistently. Otherwise, for every other disease the practical utility of animal products in the diet is described, such as the frequent recommendation of consuming the meat of desert-dwelling animals, as well as the ubiquitous application of māṃsa rasa (non-fatty meat soup).

Was Vedic culture vegetarian?

Āyurveda is a śāstra, or a teaching within the Vedic tradition, and it is not vegetarian because the ancient Vedic culture itself was not vegetarian. While this may come as a shock to many, in reality, there is so much evidence against the assertion that ancient Vedic culture was vegetarian that to state otherwise borders on the absurd. In his meticulously referenced tome, The Myth of the Holy Cow, Hindu scholar Dr. DN Jha systematically deconstructs the assertion that Vedic civilization was vegetarian. As the title suggests, the author puts forward evidence that ancient Vedic peoples did not elevate the cow in the same way as modern Hindus, making ample reference to their consumption of beef, which was especially valued as a ritual food by the priestly caste (brahmins). This irony was recently brought to light when the state of Maharashtra banned beef consumption, citing the historical importance of vegetarianism in Hindu society. Unfortunately for supporters of this move, it also brought to uncomfortable attention that many traditional brahmin communities continue to eat meat – including beef – as part of an unbroken lineage of practice that extends back thousand of years. As the great Swami Vivekananda said over a hundred years ago, “You will be surprised to know that according to ancient Hindu rites and rituals, a man cannot be a good Hindu who does not eat beef.”

Restoring the proper context for vegetarianism

Whether or not I am able to convince you that Vedic culture was not vegetarian doesn’t concern me: like any debate concerning a topic so vast, it is easy to cherry-pick one fact over another. Certainly there is evidence of vegetarian practices in the Vedic literature, but these relate to ascetic practices, and not general dietary advice. As a form a self-denial and purification, vegetarianism has long been a component of ascetic practices in ancient India. These practices ranged from meditation and yoga, to more severe methods such as plucking the hairs of the body or walking on hot coals – all as a practice to uproot worldly desire and uncover the ultimate truth. The ancientness of these practices including vegetarianism are attested to in the Rāmāyaṇam when Lord Rāma leaves the comforts of his palace to follow the path of the brahmacarya, or worldly renunciate:

“I shall live in a solitary forest like a sage for fourteen years, leaving off meat and living with roots, fruits and honey”.

– Ayōdhyā Kanda 2-20-29

The association between vegetarianism and Hindu asceticism is undeniable, but it is not an exclusive relationship, and nor was this association meant to inform the practices of everyday society. In the sacred Hindu law book, called the Manusmṛti, vegetarianism is only mentioned as a technique appropriate to the religious-minded, and not as a general practice. And even though the Manusmṛti was compiled almost 2000 years after the end of the Vedic period in India, there is nothing in it – even at its comparatively late date – to suggest that vegetarianism was a requirement for the average Hindu.

What about ahimsā?

While vegetarianism serves as a form of self-denial, important for penance or ritual purification (as in the story of Rāma), vegetarian practices are also based on the concept of ahimsā, or non-injury. As a specific form of spiritual practice, ahimsā found its greatest expression in the post-Vedic spiritual traditions of the first millennium BCE, including Jainism and Buddhism. By fully embracing the concept of ahimsā, these new spiritual movements clearly distinguished themselves from the Vedic religion, attracting new followers by critiquing the “decadent” practice of ritual animal slaughter.

Between the two, Jainism took the most radical approach to the problem of ahimsā, which in its highest expression involves the practice of sallekhanā, or starving oneself to death. While most assuredly causing the least amount of harm, sallekhanā as a spiritual goal is typically undertaken by very few people. For the vast majority of Jains, the practice ahimsā as it relates to diet allows for the consumption of dairy (as no apparent harm is caused to the cow by milking), as well as the allowance of the aerial parts of any plant as food – but not the roots (which would kill the plant). In contrast, while the practice of ahimsā is a prerequisite to spiritual advancement, simply eating meat isn’t a violation in Buddhist teachings because meat is not a living thing. Unlike Jainism, which views karma as a subtle material essence that attaches to a permanent soul, Buddhist teachings believe karma to be a function of cause and effect that relates more to intent. Thus, the Buddha would eat meat if it were given to him as part of his alms, but in order to uphold the principle of ahimsā, he would refuse to eat the food if knew beforehand that the animal had been specifically slaughtered on his behalf.

Both Buddhism and Jainism grew during the post-Vedic period, but due to its greater flexibility with regard to diet, as well as the fact that it rejected the caste system maintained by both Hindus and Jains, Buddhism became the dominant religious force in India during the later part of the first millennium. The growing and pervasive influence of Buddhism in India meant that its concepts including that of ahimsā indelibly shaped Indian society and later Hindu beliefs. Inspired by the Buddhist teachings on ahimsā, the Emperor Aśoka established a law of the land in the 3rd century BCE, enshrining the rights of animals, banning animal sacrifice, and promoting environmental stewardship. In this regard Aśoka wasn’t advocating for vegetarianism, but for greater thoughtfulness, care and consideration for all living beings.

Buddhism exerted its influence in India for almost 1000 years, and its emphasis on ahimsā as a practice had a strong influence on the Hindu revivalist movement that emerged with the decline of Buddhism. In the 7th century a Hindu reformer named Ādi Śaṅkara successfully modeled a new version of Hindu teachings that only slightly varied from Buddhism, adding the concept of an eternal god (brahman), but including the same Buddhist emphasis upon ahimsā. Gradually, this revivalist movement became a syncretic religious movement influenced by regional folk traditions, including the bhakti (devotional) movement of South India, to evolve into the dominant form of Hinduism found today in India – called Vaishnavism.

As the Hindu revival emerged during the early medieval period, India began to suffer the first wave of more than a thousand years of foreign invasion, continuing right up until the British left India in 1947. Some scholars have asserted that the ideal of ahimsā was so pervasive in early medieval Indian society that it left the country vulnerable to invasion. Certainly there was a marked difference between the character of the invading forces, whose God seemed to justify their violence and brutality, to the spiritual principles of Indian society, which valued peace, contemplation, and insight.

While there were many Hindus, including the Marathi warrior Śivaji, that attempted to fend off the invaders, the cultural traditions of India were systemically damaged during this period. Now already in decline, foreign invasion meant for Buddhism its complete eradication from India, as the hoards of Islamic warriors found little resistance from its monasteries and universities. For Hindus, it meant the destruction of a great deal of their cultural heritage, including religious monuments such as the temple at Ayōdhyā, which marked the traditional birthplace of the Hindu god Rāma.

As a response to foreign invasion, the medieval period understandably marks a period of consolidation within Indian culture, and the crystallization of a Hindu orthodoxy and its beliefs. To maintain its religious distinctiveness, and as a way to distinguish Hindus from the non-vegetarian invaders, vegetarianism was elevated as part of the Hindu cultural identity. This crystallization of Hindu teachings, however, had a dramatic impact upon the understanding and sophistication of Āyurveda. In much the same way that the sophisticated medical knowledge inherited from the Greeks and Romans by the Church underwent decline during the Dark Ages in Europe, the preservation of Āyurveda by the Hindu orthodoxy during the medieval period meant that much of the knowledge became theoretical and academic. Rational practices such as surgery almost completely disappeared from Āyurveda during this time, replaced by superstition, and a greater emphasis upon magic-religious techniques to resolve disease. In this way, the vegetarian diet as a hallmark of Hindu culture was not only associated with morality, but served as a kind of talisman against disease.

On the subject of sattva, rajas, and tamas

One frequent way used to explain the difference between vegetarianism and non-vegetarianism, as well as the practices that comprise the Hindu orthodoxy from those of the non-Hindu, is to reference the concept of triguṇa. Individually called sattva, rajas, and tamas, the triguṇa represent three distinct, yet interdependent qualitative states, each representing a difference sphere of experience. The origin of this concept is found in Sāṁkhya, a teaching considered by some scholars to be the most ancient of the Vedas. Although the original teachings of Sāṁkhya have been lost to time, it exists in redacted form as a text called the Sāṁkhya-kārikā (3-5th cent. CE), supplemented with a few references to its teachings in the Bhagavad-gītā. Sāṁkhya is particularly important to the epistemology of Āyurveda, however, and it is in classical texts such as the Caraka saṃhitā that we find the oldest surviving exposition of its teachings.

According to Sāṁkhya, sattva, rajas and tamas relate to three qualities manifest within an individuated being (called ahaṃkāra). Within this temporal state, sattva, rajas and tamas represent different aspects of individuated experience. According to the Sāṁkhya-kārikā, sattva is described as “illuminating”, giving rise to pleasure; rajas is “activating”, giving rise to pain; and tamas is “restraining”, which gives rise to delusion. Collectively, these three qualities represent the entire spectrum of experience.

Derived from the root words sat (eternal truth) and tva (thyself), sattva represents the subjective consciousness, which is only experienced in fullness through deep meditation, when the mind is turned inward and away from the compulsions of rāga (desire) and dviṣ (aversion). This is why sattva is said to give pleasure – not the temporal pleasure that fulfills desire – but rather, the bliss that comes from deep spiritual insight (saccidānanda). In contrast, tamas represents the objective, physical world, which includes our bodies, the food we eat, the earth itself, and all the stars in the universe. In Āyurveda this includes the five elements, and the three doṣa(s) that emanate from them. Between them lies rajas as the “activator”, the quality that binds sattva to tamas, drawing the illuminated consciousness outwards into the inertia of physical reality.

When the teaching of Sāṁkhya became crystalized within the Hindu orthodoxy, the concept of triguṇa became much more literal. Rather than representing the esoteric concept of the illuminated consciousness, sattva became synonymous with “goodness” and “purity”, representing the religious and spiritual values of orthodox Hinduism. Likewise, rajas became associated with “conflict” and “disturbance”, and tamas with “evil” and “contamination”. In this way, when applied to food, that which is vegetarian is automatically considered to be sattvic, whereas non-vegetarian foods are tamasic, and rajasic foods are those which stimulate the desire for tamasic foods. For example, milk and rice – two staples of Indian vegetarian cuisine – are considered “sattvic”, whereas foods like meat, fish and alcohol are considered “tamasic”. Supposed “rajasic” foods include onion, garlic and chili, which all stimulate the appetite for heavier (i.e. tamasic) foods. While this definition may seem to make sense on the basis of its own internal logic, it only does so if one ignores the original teaching of Sāṁkhya and Āyurveda. According to Caraka, the word “sattva” is synonymous with the mind, and if we accept this definition, it cannot be possible for food also to be a product of sattva.

Each of us must consume food to nourish our bodies, and thus both food and the body relates to the quality of tamas. It is impossible to say that one food is “sattvic” and another is “tamasic”, when in truth, all foods are tamasic, and are eaten precisely for these tamasic qualities, i.e. to nourish and sustain our tamasic bodies. When a tamasic object such as food is elevated to the quality of sattva, we are practicing a subtle form of spiritual materialism, in which object become confused for subject. Since the medieval period in India, Hindu beliefs and practices have frequently reflected this misapprehension, devolving from the symbolic, sacred meaning of objects and the impression this is meant to convey to the mind, to the elevation of these objects as the embodiment of the spiritual experience itself.

When I have raised these issues before, one frequent argument I am met with is that I must be saying that food has no impact upon consciousness. This conclusion, however, similarly reflects the ignorance of someone that doesn’t fully comprehend the interdependent nature of triguṇa. Just because food and mind are not the same thing, it doesn’t mean that food cannot impact the consciousness – obviously it does – just as anyone who has perhaps eaten too much chili pepper or horseradish can attest to. But this effect is not a unique property of food, as anything within the realm of tamas can impact the mind. How do you feel on a rainy day – a little depressed and sad perhaps? What if you had an argument with someone – do you feel angry? Or what if you won the lottery? Would it change how you feel? There is no denying that tamasic experiences can and do impact the equilibrium of the mind (sattva), but they do so most powerfully when we confuse subject (i.e. the mind) for object (i.e. physical reality). For example, if someone does something we don’t like, and we get angry, is that person the cause of our anger, and thus responsible for it, or is our anger purely an emanation of our consciousness?

Confusing vegetarianism with spirituality

During the Buddha’s lifetime, he had a follower named Devadatta who wanted to change some of the teachings. Specifically, Devadatta believed that the vegetarianism practiced by other religious sects, such as the Jains, should be incorporated into the Buddhist monastic code. While upholding the principle of ahimsā, the Buddha rejected Devadatta’s request, which eventually resulted in his expulsion from the saṃgha. The reason the Buddha rejected him is because Devdatta was fundamentally confused, wanting to turn the teaching into a cult of materialism that elevated vegetarianism as a spiritual goal, once again, confusing subject for object. Likewise, throughout the spiritual history of India, the great adepts have rejected spiritual distinctions with regard to diet, including Shirdi Sai Baba, who sought to overcome communal politics by embracing a practical and egalitarian approach to food. Consider as well, what the Sikh holy book, called the Guru Granth Sahib, says on the matter:

“The fools argue about flesh and meat, but they know nothing about meditation and spiritual wisdom. What is called meat, and what is called green vegetables? What leads to sin? It was the habit of the gods to kill the rhinoceros, and make a feast of the burnt offering. Those who renounce meat, and hold their noses when sitting near it, devour men at night. They practice hypocrisy, and make a show before other people, but they do not understand anything about meditation or spiritual wisdom. O Nanak, what can be said to the blind people? They cannot answer, or even understand what is said.”

My intent in writing this post has not been to hurt anyone’s feelings. Vegetarianism is an ethical and moral choice, and despite what conclusions might be drawn from my writing, I have a great deal of respect for this choice. I applaud the efforts of animal rights activists, and am fully behind the effort to deconstruct the industrial food model that treats living creatures as nothing more than commodities. But the choice of vegetarianism is just that – a choice – not an imperative. There is nothing in Hinduism or Āyurveda that mandates vegetarianism, despite the fact that almost all college-trained physicians of Āyurveda recommend a vegetarian diet. To this day, physicians will directly contradict or modify the practices of Āyurveda to promulgate the mistaken belief that a vegetarian diet is “healthier”, or is somehow intrinsically better to achieve mental balance. As we can see with the issue I raised with regard to the problem of vitamin B12 deficiency in vegetarian communities, the all-pervasive belief that vegetarianism is superior diet is a kind hubris imposed onto Āyurveda, limiting its practical utility, and causing irrevocable damage to its integrity.

The issue of vegetarianism in Āyurveda is a metaphorical sacred cow that obfuscates its authentic history and practice, and forces it to become nothing more than a pale replica of itself. The reality is that Āyurveda is for everybody, regardless of diet, faith, gender, age, culture, geography, or climate. According to tradition, the knowledge of Āyurveda is built into the very fabric of matter itself, and in this way, is a part of us all – even if we don’t know it. Āyurveda is a system of knowledge that allows you live in concert with dharma, or the natural rhythm of life, no matter where you live: whether its the lush tropics of south India where being a vegetarian is very easy, or the frigid steppes of Tibet, where being a vegetarian isn’t even a possibility. My hope in addressing this issue is to reopen the dialogue around diet, restoring Āyurveda to its proper state: resplendent in its grounded, earthy wisdom.

Hello, can you explain why vegetarianism would have been recommended for psychosis specifically?

Hi Lisa – please see: https://dogwoodbotanical.com/ayurveda-diet-psychosis/

Speaking on the issue of sattva, rajas and tamas… Do you know anything of the origin of strict brahmins avoiding onion and garlic, if they cannot be clasified as “tamasic” ? I have even heard from one teacher (who was not Jain) that “shakahara” wasn’t specifially about avoiding non-vegetarian foods, rather it was the avoiding of any foods of a “downward-flowing-energetic nature”, hence garlic, onions, moosoor dal (red lentils), any root vegetables, mushrooms and any form of animal flesh, as these are supposedly somehow more “downward” in nature than other plant-foods. He also mentioned the “tamasic” nature of any food prepared by a menstruating woman.

Could the classification of certain foods as sattvic, rajasic or tamasic not be referring more to their specific effect upon the consciousness under particular circumstances, rather than the characteristic qualities of that particular food by itself ? For instance, consuming meat with a strong digestive system may be beneficial to one person and cause less disturbance on their mind as a vegetarian diet would (thus meat being considered “sattvic” for that particular person)… however for someone with weak digestion, a non-veg diet would be a cause for a sense of inertia, thus having a “tamasic” effect on their mind.

Understanding that food in of itself rests within the realm of tamas, could we not claim a hierarchy of sattva, rajas and tamas even within that realm ?

Hi Lexie

These beliefs are common to the form of Hinduism that emerged during the medieval period, and aren’t found in earlier times, and nor are these associations found in classical Ayurveda. It sounds to me like your teacher applies a hybrid system that synthesizes medieval Hindu beliefs with Jainism, but empirically, I do not believe these statements are supportable. Any type of food can affect the mind, but it’s not possible to say that one food will always affect different people in the same way. If you’re not used to taking garlic, then it makes quite an impression – likewise, if you do consume it habitually, it will have less of an effect. In some, garlic will promote irritation or burning sensations, but in someone else, garlic improves digestion and enhances motility. And consider milk for e.g. – it’s no good saying that its “sattvic”, when other people who cannot tolerate experience “rajasic” symptoms such as bloating, gas, diarrhea, joint pain, skin disorders etc. His additional statement that menstruating women make food tamasic is really just a form of mysogyny in my opinion. I have observed my wife cooking when she’s menstruating, and there is no discernible difference in her cooking, although if you ask her, perhaps she might say she’s rather go cuddle up with a book. In this way, it could be that the source of this myth comes from women themselves – who rather than being contaminated or ritually impure, are simply not functioning at 100{6921d8d6427042db5aa411e0d401cbd175b775e2ec65ab7940ca136572bc3362} and maybe need a night off from cooking and housework.

With regard to your second paragraph, i.e. is there a “hierarchy of sattva, rajas and tamas” within tamas… in short, no, because tamas is tamas, and sattva is an entirely different sphere of experience. In Ayurveda, we already have a way to understand all these effects, without having to use what is a highly prejudicial system of morals to guide food consumption. If the food creates heaviness and poor digestion, this is called ajirna, or indigestion. If this happens, then measures are taken to increase agni and ensure that the food is adequately digestible… and unless the digestion is very very weak, there are ways to prepare meat that it could be digested by anybody, hence the frequent recommendation of mamsa rasa, or meat soup, applied in Ayurveda for a multitude of health issues.

I am a bit confused by this article. I know that Ayurveda is not strictly vegetarian, but from what I’ve learned about Ayurveda is that meat was not to be eaten regularily, but only in certain circumstances like being emaciated, weak or convalescing. Also that any meat consumed was to be obtained by traditional hunting methods and living in it’s natural habitat and environment, otherwise it was unwholesome, or toxic if the animal had been eating food not part of it’s natural diet. You would be hard pressed to find meat that lived up to those standards these days. From what I’ve read, authentic ayurveda dietary advice is purely vegetarian, except in those circumstances. It makes sense since biologically we are not meant to eat meat. Our teeth cannot tear apart flesh, and are more the teeth of a herbivore. We cannot digest raw flesh, our digestive tracts are long, not like that of a carnivore who have short digestive tracts and much stronger digestive acids. Not only that but there is so much research these days about how a plant based diet can prevent, if not reverse some diseases. I have taken plant based nutrition certification courses under medical doctors, and all of the research that they and others have done clearly shows that not consuming meat is the best for our bodies. Just knowing what I do about Ayurveda and food as medicine it makes so much more sense for it to be vegetarian than not, especially the meat that is available these days. I’m also confused about how this article is contradictory to what I’ve read about fresh vegetarian food being sattvic. That makes much more sense to me. I obviously do not know as much about Ayurveda as you, but this just seems to be the opposite of everything that I have ever learned before.

But the approach that I really don’t understand is when you talk about Buddhism and Ahimsa. I am Buddhist, and Buddhism is the reason I am vegetarian. I am actually vegan because of the treatment of animals in the dairy industry, but Buddhism has everything to do with that and it is absolutely spiritual. I realise there are different schools of thought when it comes to Buddhism, but The eightfold path is very clear. You must not intentionally kill a living being. It even goes further that you must not work somewhere that harms animals, like a butcher for example. There is no getting around this, when you go to a store to purchase meat, it has been intentionally killed for you. I know not every buddhist is vegetarian, but that is because they are not following the eightfold path to enlightenment. To me, being vegetarian is the basis of Buddhism. It encompasses love, compassion, peace. You cannot have this while consuming the flesh of a dead animal that has most likely lived a life of torture and misery simply so you could have a few minutes of “pleasure”. We will never truly have peace until we stop killing. I have also taken my yoga teacher training to deepen my practice and studied the philosophy. Another point that is very clear to me is ahimsa, non-violence. I don’t see how it could be taken any other way than not killing. I don’t know anybody else that doesn’t see it that way either. Not consuming meat isn’t about self denial at all. I’m not denying myself of anything. Eating meat was a habit. Completely unncessary and causing so much harm to the animals, myself and the environment. Not eating meat is a very spiritually uplifting. I have never felt better, my mind and conscience have never been so clear. Both Buddhism and Ahimsa are very much about living a non-violent, loving, compassionate life and being connected to every part of nature. I just don’t see how either could be taken any other way.

>>>>I am a bit confused by this article. I know that Ayurveda is not strictly vegetarian, but from what I’ve learned about Ayurveda is that meat was not to be eaten regularily, but only in certain circumstances like being emaciated, weak or convalescing. >>>>

Hi Michelle,

Where is this described in classical texts such as Charaka, Sushruta, or Vagbhata? Please research this further and report back with your findings. As well, perhaps enquire into the meat-eating brahmin communities of Kerala, or the Kashmiri brahmins, who also eat meat, or the Bajracharya physicians of Nepal. Ask too about the dietary practices of the Tibeto-Ayurveda physicians that live on the Tibetan Plateau, particularly in the dead of winter, or what its like to spend a winter in northern Afghanistan, the original home of the most ancient school of Ayurveda at Takshashila.

Vegetarianism has a purpose, but it is not a requirement nor a preferment of Ayurveda for very good reason.

>>>>Also that any meat consumed was to be obtained by traditional hunting methods and living in it’s natural habitat and environment, otherwise it was unwholesome, or toxic if the animal had been eating food not part of it’s natural diet. You would be hard pressed to find meat that lived up to those standards these days.>>>>

I disagree. Do you only obtain your food from a wild environment? If not, then you are getting it from agriculture, whether derived from mono-cultured crops, or from a tiny organic farm. Likewise, you have a choice of where to obtain your meat. I suggest that all food be obtained from a clean, wholesome environment. If you are looking for a source of clean meat, I suggest that you start with http://eatwild.com/.

>>>>From what I’ve read, authentic ayurveda dietary advice is purely vegetarian, except in those circumstances. It makes sense since biologically we are not meant to eat meat. Our teeth cannot tear apart flesh, and are more the teeth of a herbivore. We cannot digest raw flesh, our digestive tracts are long, not like that of a carnivore who have short digestive tracts and much stronger digestive acids. Not only that but there is so much research these days about how a plant based diet can prevent, if not reverse some diseases. I have taken plant based nutrition certification courses under medical doctors, and all of the research that they and others have done clearly shows that not consuming meat is the best for our bodies>>>>.

To be quite frank, this is the same nonsense I have heard reverberating in the natural health field for decades, but just because an error is constantly retold and repeated, doesn’t make it more true. I am sorry, but it is clear that you haven’t done the requisite research. What I say about the suitability of cooked meat in the human diet is simply what the evidence states: that human brain development was dependent upon nutrient dense animal foods that were cooked or denatured in some fashion so as to render them more assimilable. The archeological record clearly shows that we have been doing this for at least a half a million years, and maybe much earlier. Hopefully you can appreciate how this is more than enough time for humans to have become conditionally dependent on eating cooked meat, just like they have became dependent on wearing clothing, living in shelters, building fires, boiling their water, fashioning tools, etc. As I explain in Food As Medicine, cooking and eating meat is exactly why we have the very large brains we do, complemented by tiny weeny little digestive tracts. We are not like any other primate for this reason, but if closest to any primate, it is to either the chimpanzee or bonobo, both of which seek out animal prey on a regular basis.

>>>>Just knowing what I do about Ayurveda and food as medicine it makes so much more sense for it to be vegetarian than not, especially the meat that is available these days. I’m also confused about how this article is contradictory to what I’ve read about fresh vegetarian food being sattvic. That makes much more sense to me. I obviously do not know as much about Ayurveda as you, but this just seems to be the opposite of everything that I have ever learned before. >>>>

As far as I can see, the only reason you can’t accept my argument is because it doesn’t conform to what you have been told. But then ask yourself – why exactly did I bother to write the article? I can assure you that it is not to attack vegetarianism, or anyone’s particular choice of diet, but to address the misconception that Ayurveda has anything to do with vegetarianism. As I stated, this belief is actually a subtle form of spiritual materialism that can be easily deconstructed. Perhaps you find my argument difficult because it exposes a contradiction, but that was exactly my intent. Your confusion arises because your original perspective wasn’t firmly rooted. You can either retreat to that contrivance, or admit the facts as they arise. I can only hope that you think a little more deeply on this.

>>>>But the approach that I really don’t understand is when you talk about Buddhism and Ahimsa. I am Buddhist, and Buddhism is the reason I am vegetarian. I am actually vegan because of the treatment of animals in the dairy industry, but Buddhism has everything to do with that and it is absolutely spiritual. I realise there are different schools of thought when it comes to Buddhism, but The eightfold path is very clear. You must not intentionally kill a living being.>>>>

The eight-fold path is a teaching directed to the aspirations of a monk, or a nun, someone that is willing to commit all their effort to the attain of enlightenment. The Buddha never required this of anybody that didn’t enter into the Sangha, and make this personal sacrifice.

So ask yourself: are you a monk or a nun? If so, then reasonably there is a basis for your argument, but this is a personal choice and nothing more. The Buddha didn’t make any requirements around diet, and himself ate meat whenever it was offered in good faith. As I pointed out, an early schism occurred in Buddhism during the Buddha’s lifetime, when Devadatta tried to turn it into a cult of vegetarianism. You might disbelieve this, but it is true nonetheless if you care to investigate the tradition a little more deeply: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Devadatta#Therav.C4.81da_account

Likewise if someone is a menstruating, pregnant or lactating female, and/or if you live in a cooler climate where local sustainable vegetarianism is impossible, or if you are a child, an elderly person, or someone that is predominantly vata – is your personal choice enough to tell all these people they can’t eat meat? Ayurveda does not say that. The Buddha did not say that. So on what basis do you judge others?

>>>>It even goes further that you must not work somewhere that harms animals, like a butcher for example. There is no getting around this, when you go to a store to purchase meat, it has been intentionally killed for you.>>>>

Yes, the animal has been killed with the intention that someone might eat it, but not necessarily me, or you, or whoever randomly happens to wind up with it when it is sold at the butcher. You attribute an essence to something that doesn’t exist. Meat doesn’t have karma – unless in fact you are a practicing Jain. Are you a Jain? You said you were a Buddhist. The Buddha makes this issue very clear in the earliest of Buddhist writings. This is a good summary:

http://buddhasrealteachings.blogspot.ca/2014/05/the-buddhas-view-on-meat-eating_9541.html

As well, please visit Buddhist countries like Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet, and report back whether or not the regular folk that call themselves Buddhist, if they traditionally eat meat in their respective societies.

Please note that my writings are not meant to contradict your deeply held, personal convictions. My comments are addressed to a greater issue, which is to correct a misapprehension that I have seen cause a great deal of harm. I see many patients and students that are vegetarian and vegan, and especially women, that exhibit the classic failure to thrive symptoms, increasing their risk of and suffering from chronic degenerative diseases. By this I am not saying meat eaters are healthier, because most are ignorant and don’t know how to eat in a healthy fashion generally. Your particular choice to be vegan isn’t predicated on health, nor biology, nor human tradition: it is an ethical choice. But that ethical choice has absolutely nothing to do with Ayurveda. Please understand the difference.

http://everydayayurveda.org/live/how-to-eat-meat-recipe-included

This newsletter was interesting too!

Todd, thank you so much for this academic, but very readable discussion of this topic. Having trained by apprenticeship in India, through study of Ashtanga Hrdayam, I find it completely perplexing that Ayurveda practitioners have the impression that vegetarianism is inherently “better.” I recently wrote a piece for Huffington Post (I’m a Yogi, and I Eat Meat), that drew a fair bit of vitriole–mostly on FB. (Apparently I’m “misguided” 🙂 ).

I think that a huge part of the problem is that modern, Western yoga practitioners somehow have the idea that Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra (a text regarding Raja Yoga) is the definitive guide on conduct for a practitioner of Hatha Yoga. Taking that further, the limited understanding of ahimsa as, literally, “killing” cuts off the possibility of more nuanced and sophisticated discussions of ahimsa as “not creating separateness.” But that’s a whole other discussion. 🙂

In addition, Hatha Yoga and Ayurveda, while they come from the same cultural heritage, actually have slightly different end goals. For the yogi, on retreat, in pursuit of a particular (more or less transcendental) experience, it may be true that vegetarianism IS more ideal. However, as you point out, that may not be true for a large majority of “regular” folks, whether or not they also practice Hatha Yoga. I also have found it challenging to work with these misconceptions of my clients–particularly vata-provoked, menstrually-disordered women.

From my understanding, ultimately a yogi is a person who makes a commitment to check their experience against their inner knowing and doesn’t take anything at face value. A yogi doesn’t follow a doctrine or a code of ethics that has been imposed from outside, but seeks to find harmony and resonance from within. An Ayurved is a “worshipper of life;” one who seeks to nourish and protect the flame of wisdom as it expresses through our aliveness. Sometimes that includes eating meat. For me there is no contradiction there, and no judgement.

Thanks again for your earnest efforts to cut through the BS.

Todd-Not to open a can of worms on this article- I looked up the quote that you listed from the Ayodhya Kanda- in Valmiki Ramayana- 2-50-44 “kusha ciira ajina dharam phala muula ashanam ca maam |viddhi praNihitam dharme taapasam vana gocaram || 2-50-44

Translation as provided – viddhi= know; maam= me; praNihitam= as under a vow; taapasam= to be an ascetic; kushachiiraajinadharam= wearing the robes of bark and deerskin; dharma= and by piety; praNihitam= I am determined; vanacharam= to live in the forest; phalamuulaashinam= eating fruits and roots.”

“Know me as under a vow to be an ascetic, wearing the robes of bark and deerskin and by piety, I am determined to live in the forest by eating roots and fruits only.”.

I would certainly appreciate your source of this quote where the meat portion is listed. While I am on the fence about either perspective, I continue to be challenged by the viewpoints and contrasts presented as a student Ayurveda where we consider the wholistic approach to human being as an expression of Consciousness and the 5-elements VS. the Western Cartesian approach of B-12 deficiency which is breaking down the building blocks of our physical structure. Unless we are using B-12 levels as a metric to measure how the doshas are out of balance and are reflected in the Guna expressed as a deficient B-12.

Hi Gayathri – thanks for writing in. You are correct – but the problem is not the quote, but my citation. Instead of 2-50-44, I should have put 2-20-29, which reads:

चतुर्दश हि वर्षाणि वत्स्यामि विजने वने | मधु मूल फलैः जीवन् हित्वा मुनिवद् आमिषम् || २-२०-२९

caturdaśa hi vatsyāmi vatsyāmi vijane vane | madhu mūla phalaiḥ jīvan hitvā munivad āmiṣam

caturdaśa = fourteen

vatsyāmi = years

vatsyāmi = I shall live

vijane = bereft of people

vane = in forest

madhu mūla phalaiḥ = with honey; roots and fruits

jīvan = living

hitvā = leaving off

munivad = like sage

āmiṣam = meat

Although my citation was in error, I believe my thesis is not, and thus all of my assertions remain valid. There is no indication in Ayurveda that vegetarianism is to be generally recommended, and likewise, there is no general injunction against its consumption in important Hindu texts such as the Manu Smrti.

Dear Todd,

Thank you for this insightful article, I appreciate you sharing your perspective.

Does Ayurveda provide ethical considerations regarding slaughtering and eating meat? For example, are there circumstances when it is ethical and when is it not, and is there a ritualized way to slaughter an animal?

Also, what would be the Ayurvedic explanation of a B12 deficiency and what solutions would it suggest? And what about the ascetics who became vegetarian, surely they must have also become sufficient in B12?

That said, there are examples of people who have lived for many years without eating, and claim to be sustained directly from spiritual energy. How would Ayurveda explain this? For example , this man:

http://www.collective-evolution.com/2013/07/04/a-man-has-not-eaten-or-drank-any-liquids-for-70-years-science-examines-him/

Thank you for your time.

Kind regards,

Morgan.

Hi Morgan

Ayurveda does not provide for ethical considerations in the slaughter of animals. For Hindus, this is addressed in texts such as the Manu Smriti. For other religions, it is covered in their respective traditions, e.g. Buddhist, Jain, Muslim, Christian, atheist, etc.

Ayurveda doesn’t have a specific explanation of a B12 deficiency because vitamins are not described. What Ayurveda talks about is a wholesome diet, which itself is predicated on several factors, such as deha (climate), kāla (time and season), rāśi (quantity of food), prakṛti (quality of food), karaṇa (preparation of food), saṃyoga (combination of foods), upayoga (consumption of food), and upayukta (recipient).

As for ascetics, they are not eating to thrive – they are eating as a baseline necessity to maintain the body on their spiritual quest. But this is not the nutritional ideal, nor any more valid than equating the dietary needs of a half-naked ascetic and a lactating mother. Nonetheless, in all the Indian ascetic traditions, milk or dairy of some kind is an acceptable food, and this is a source of B12. For the Buddha and his followers, they ate whatever was offered in their begging bowl, and thus frequently ended up eating meat. This is clearly described in the ancient Buddhist literature. But not all ascetics share the same philosophy, values or methods.

As for Prahlad Jani, I believe that this has in large part been dismissed as a hoax, as the research results of a 15 day study conducted on this fellow were never peer reviewed nor released for public scrutiny. You can read both sides of the debate and decide for yourself, but so far, I see nothing to get excited about.