Paths of Perception

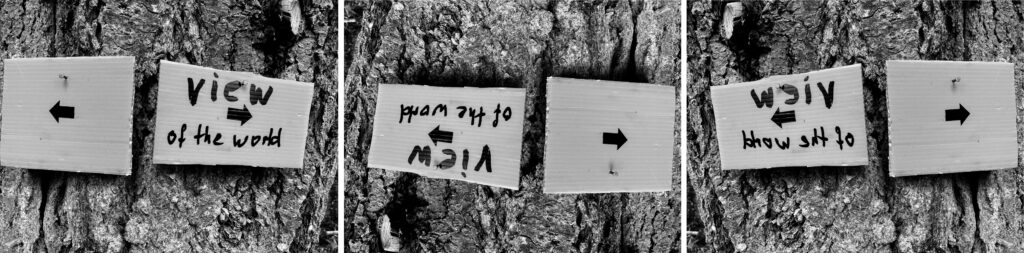

You’ll encounter these signs about 10 minutes if you follow a little trail off the Lund highway, across from the Tla’amin Convenience store on the southern edge of Teeshoshum (t̓išosəm) village. If you veer right, you’ll climb up a bluff that overlooks my little community of Wildwood, offering a rarely appreciated view of its backside — what I whimsically call the “butthole” — a natural wetland adjacent to a decommissioned sewage lagoon. Should you take the trail to the left, it loops back to the start, or you can take a branch that leads up to Little Sliammon Lake.

I pass by these signs every time I walk the trail. At first, I thought it quaint to imagine that this view could encompass the whole world, a notion that probably seems true for some long-term residents that have seldom explored beyond this community. However, with each repeated encounter, in my mind these signs morphed into something different, as a metaphor representing the dichotomy of perception and choice.

On one side – the “right” side – we are promised a “view of the world,” a perspective shaped by our collective experience. This is the “mainstream” viewpoint, rooted in shared beliefs, common sense, or scientific consensus, reflecting how most people around us interpret the world. In contrast, heading in the opposite direction is an alternate path, leading to something unlabeled; perhaps underappreciated, unconsidered, or even unknown.

These diverging paths mirror the dual nature of perception and choice inherent in our decisions, underscoring that neither path encompasses the whole truth. Any proposition can be met with a counterargument. According to Aristotle, this is the first rule of logic: that if an entity can be said to exist (A = A), it inherently implies the existence of distinct entities (A ≠ B). Not only does this acknowledge the existence of a thing, but also the manifold reality in which we live.

While it’s easy to admit the diversity of this earthly realm, managing the cacophony of our minds is not so straightforward. F. Scott Fitzgerald once suggested that “true intelligence” is the capacity to entertain contradiction, but he fails to capture just how difficult and painful this experience can be. Most of us find having competing narratives in our mind difficult to manage, and when our understanding of the world is in conflict, it creates a painful and confusing state of cognitive dissonance. In surveying my life and from the feedback of others, it seems that for many of us this state of dissonance has become notably worse since 2015, with an increasing prevalence of technology in our lives, to the breakdown of socio-political norms.

For most of us, when faced the dissonance of two opposing views, our thinking typically evolves in one of two ways. Either we resolve the contradiction by reactively cleaving to one perspective, or we turn the notion in our minds over and over, hoping to find some kind of synthesis. While the former always raises the possibility that we’re dead wrong, and hence risk ensuing disaster, the problem with the latter is that we might never arrive at a synthesis. If such a state is allowed to persist, it can undermine confidence and erode the agency of choice, giving rise to problems such as anxiety and depression. And even if we can finally resolve the contradiction through compromise — often the best case solution — the result still feels at least a little painful, and sometimes a lot.

Navigating the complexities of perception and choice is arguably humanity’s most daunting challenge. When faced with this problem, the Chinese Taoist philosopher Lǎozǐ suggested we cultivate the state of becoming — like an “uncarved block” of wood (pǔ):

The world is formed from the void,

– Dàodéjīng, Chapter 28

like utensils from a block of wood.

The Master knows the utensils,

yet keeps to the block:

thus they can use all things.

In this passage, Lǎozǐ encourages us to focus on the tree itself rather than the signs nailed to it. He asks us to see beyond the superficial to reveal the essence of nature itself, rather than the constructs we attach to it. In the face of difficult decisions, he teaches the value of choicelessness, through contemplation and acceptance — however perplexing — before proceeding to action. Cultivating this mindset, Lǎozǐ asserts, the dào (truth) is naturally illuminated within us.

But as important as it is to cultivate this state of choicelessness, the world often demands action. Even when, and especially if, our goal is peace and equanimity, there are always forces that seek to undermine this. Called evil by some but frequently rooted in little more than blind ignorance, injustice is a perennial issue requiring us to be vigilant and even severe.

Consider the story of Arjuna and Kṛṣṇa from the Bhagavad Gītā, on the night before the battle in which Arjuna goes to war with his kinsfolk. Seeing family on both sides of the battlefield, Arjuna is filled with doubt and confusion. In the midst of this crisis, his charioteer Kṛṣṇa impresses upon him the importance of upholding his duty, or dharma. Arjuna’s kinsfolk are driven by greed and jealousy, resorting to deceit and treachery to gain personal advantage, and Kṛṣṇa advises him that he has no choice but fight. Given the pain of going to war with his family, Kṛṣṇa counsels Arjuna to fulfill his duty as a warrior with a detached and selfless mindset. In this way, the story of Arjuna teaches us that we can act and fulfill our duty even from a place of choicelessness.

According to the Bhagavad Gītā, the most important consideration behind effective action is the support of dharma. Understood in various contexts to mean different things, in the Gītā as articulated by Kṛṣṇa, dharma is action that seeks to alleviate suffering. This premise is based on the most ancient of Vedic teachings, called the Sāṅkhya darśana, which in its oldest form denies the relevance of god: there is nobody coming to save you. Thus, abandoned to the constant churning of this wheel of birth and death, in a world filled with ignorance, hatred, and greed, Sāṅkhya teaches that greatest purpose and meaning of life lies in the alleviation of suffering. But unlike the strict pacifism of Sāṅkhya, the Gītā also teaches that we sometimes must fight, and even sacrifice our lives, to achieve this purpose. Although imperfect, a good example of this is the sacrifice our forebears made during WWII, to secure the future peace we now enjoy — not unlike the sacrifice Ukrainians have been forced to make.

I’ve walked past these signs now for the last year, and each time it triggers some thought about the dichotomy they represent, and how this argument between mainstream and alternative views has become so polarized these last few years. As someone labelled as an “alternative” practitioner, I know all about marching to the beat of a different drummer, and how exhausting it can be. And, after almost 30 years of practice, I also know that whatever principles we start with, life forces us to acknowledge nuance and complexity.

In a world bound up in argument and counter-argument, amplified by a digital media environment that is algorithmically engineered to elicit outrage, I think we desperately need to cultivate Lǎozǐ’s advice: to step back from the fray and in any debate try to find the complete view — which often means not taking any view at all.

But when resting in this state of choicelessness, when forced to make a decision because the world requires us to act —whether related to personal, societal, or global issues— the Gītā also tells us we must consider our ultimate duty. Thus, whether contemplating vaccines, social justice issues, or contemporary crises such as the ongoing conflict in Gaza, for me the only choice is the one that alleviates and prevents suffering. In the moral haze of influencer culture we’ve become accustomed to, this teaching especially urges us to judge actions not by their intention or rhetoric, nor by marketing and propaganda, but by their outcomes, in the words of Jesus: ‘You will know them by their fruits.’

Responses