Herbal medicine and COVID-19

Shortly before we began the Ayurveda in Nepal program in February, details on what was initially called the Wuhan virus were just beginning to emerge, and I began to receive a lot of questions about what people should do to prepare for it. Given that I’ve been so busy in the Nepal program I haven’t had much time to write anything on the subject. Now that the program is over and I’m spending a few days at the beach in Kerala, I have a little more time to share my thoughts on COVID-19. Part of my hesitation is that there has been so much written on the subject that I really didn’t want to play into the whole “disaster porn” narrative that is so prevalent. Now, as more facts have emerged, I feel it’s probably a good time to share my thoughts on the subject.

What is the coronavirus?

Although I don’t pay too much attention to social media, there is a lot of speculation on the source for the coronavirus including a conspiracy theory peddled that it is a bioweapon developed by either the Chinese or US governments to target each other’s population. It’s easy to understand that such conspiracies may develop simply because the field of virology is relatively recent, and viruses occupy a weird place in biology, as obligate intracellular parasites that aren’t actually living, but like a demonic force, require a living body in which to replicate itself. Not completely understanding what viruses are and how different strains arise is a cause of much of the ignorance and fake news that is so pervasive on the internet.

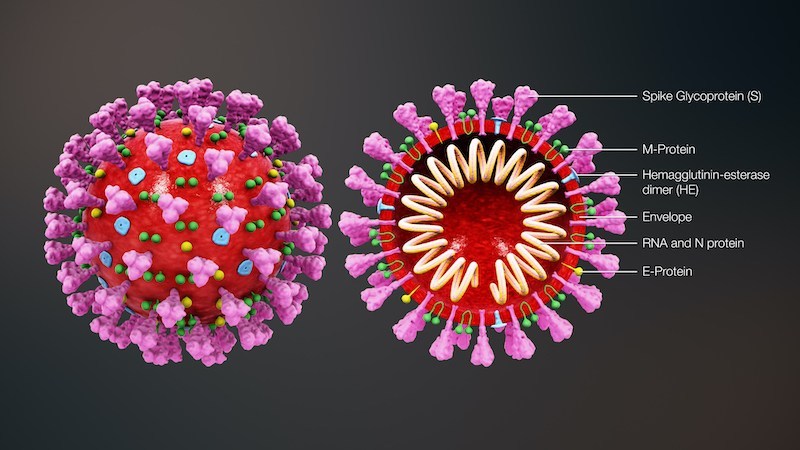

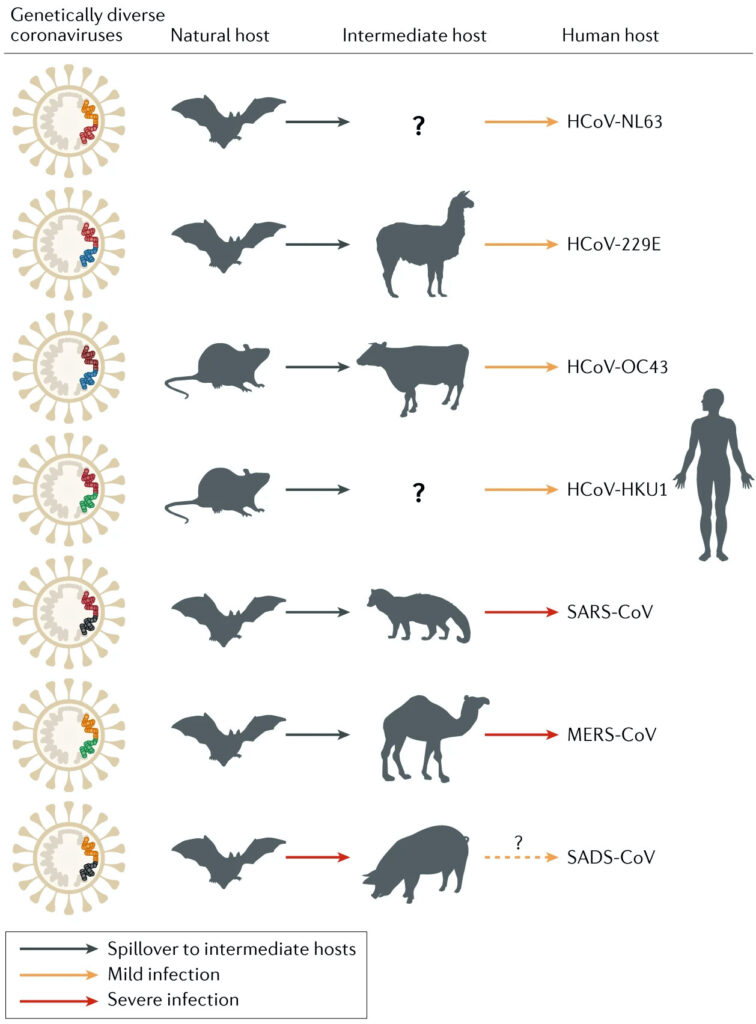

As one among many different types of viruses, the coronavirus (CoV) was only discovered in the 1960s, but has likely been around for millions of years, naturally hosted in bat, rodent, and bird species, thought to spread to humans through intermediate hosts such as pigs, camels, civet cats, and cattle. It derives its name from a fringe of viral particles that surrounds the virus, giving it the appearance of a crown (“corona” in Latin). Soon after it’s discovery it was found that some strains of CoV were a viral factor in the development of the common cold, causing relatively mild symptoms such as runny nose (rhinitis), sore throat, fever, and cough, but in immunocompromised people can progress to cough and pneumonia, and can even be fatal. As virology has progressed other the last 60 years a number of other strains of CoV have been identified and their genome mapped. Each season during winter and spring when infection becomes more common, scientists see these same CoVs causing problems such as cold and flu with some regularity.

Every so often, a new strain of CoV makes itself known. In 2003 a novel strain of CoV later identified as SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) resulted in severe illness marked by systemic symptoms of muscle pain, headache, and fever, shortly followed by the onset of cough, difficulty breathing, and pneumonia. Although only about 8000 people were infected over 2003-04, it had a fatality rate of about 10%, and in patients over the age of 60 a mortality rate that approached 50%. Likewise in 2012 another novel CoV developed in the Middle East, later identified as MERS (Middle-East respiratory syndrome) CoV that caused even more severe illness, but because the virus wasn’t shed as easily, the transmission rate was much lower. Unlike SARS, however, which eventually became dormant, MERS continues to cause illness, and as of December 2019, there have been almost 2500 confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infections since it first appeared, with a mortality rate of approximately 34.5%.

Like SARS and MERS, the COVID-19 is another novel coronavirus that scientists hadn’t seen before, and like the 2003 SARS virus was thought to have originated in China. Specifically, it is thought that COVID-19 developed in one of the so-called “wet markets” in Wuhan province in China, where vendors selling exotic wild animals such as civet cats are packed into a small area. Due to lack of proper hygiene or regulation, it is a perfect breeding ground for contagious illness. The virus began to be active in humans in late 2019 and the number of infections grew dramatically over a short period of time. By early 2020 the viral genome had been sequenced and identified as being closest to a SARS-like coronavirus strain naturally found in bats called BatCov RaTG13. Initially the virus was named SARS-CoV-2 but due to the public confusing it with the 2003 SARS virus, the WHO officially named it COVID-19 on Feb 11 2020.

Update on the Lab-Leak Theory: Recent assessments indicate that while zoonotic spillover from bats or via an intermediate host still carries the most weight, a laboratory-related incident cannot be dismissed outright. The World Health Organization’s expert panel (SAGO) reaffirmed that, based on current evidence, zoonotic origin is most plausible, but both lab‑leak and natural spillover remain valid possibilities pending more data. Several U.S. intelligence agencies, including the CIA (with low confidence), FBI (moderate confidence), and the Department of Energy, have leaned toward the lab‑leak hypothesis. Likewise, Germany’s BND reportedly estimated an 80–95% likelihood of a lab‑related event occurring.

We’ve all born witness to the rapid spread of this virus in China, and as the weeks have progressed, we are now seeing the illness spread well beyond its borders including other Asia countries (e.g. South Korea), the Middle East (e.g. Iran), Europe (e.g. Italy) and now North America. Only in the last few days has the WHO declared the illness a pandemic and this has predictably triggered some irrational behaviors by various governments, including the US, which in turn is having a significant impact upon the global economy. Many countries dependent on tourism for example, have seen a dramatic decline in visitors, and there is a good chance – especially with the recent losses in the stock market – that COVID-19 will trigger a major recession. The upside, however, is that all this inactivity has had a favorable impact on the environment – particularly in China – where the government’s response to COVID-19 is thought to be responsible for a 25% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Hopefully this not a sign of what needs to happen to bring the human relationship with the earth back into balance.

While I do think there is reason for concern, there is clearly a lot of fear when it comes to COVID-19, and I believe some this is due to the WHO and media outlets reporting an artificially high fatality rate. In a normal year, influenza has a fatality rate of about 0.1% in developed countries such as the US, but according to WHO data, the fatality rate for COVID-19 is hovering around 3.4%. If this is the true mortality rate for COVID-19 this would be very worrisome indeed, but it appears that this is not an accurate reflection of the actual number of cases. The data I have seen suggests that most of the confirmed COVID-19 cases are moderate to severe in nature, and like influenza, seems to be affecting primarily older patients that have pre-existing conditions including cardiovascular, respiratory, or immunological issues. Unlike the H1N1 influenza virus that was responsible for the pandemic of 1918, or the more recent “swine” flu of 2009, COVID-19 doesn’t seem to cause a “cytokine storm”, where the immune systems of otherwise healthy individuals becomes hyper-stimulated and triggers severe illness. In fact, it appears that more than 80% of people infected with COVID-19 experience very mild to no symptoms at all. Early on in the COVID-19 story, epidemiologists such as Dr Michael Mina were suggesting that the true infection rate in China was well over a million, which if accurate, brings the fatality rate for COVID-19 down to about the same as seasonal influenza.

While there are still a lot of unknowns, the closest thing we have to a controlled study is the pattern of COVID-19 infection on the cruise ship the Diamond Princess, which shortly returned to port in Yokohama just after it was discovered that a passenger had the illness. Of the 3,711 passengers and crew members on board, 705 became infected (~19%), with about half showing symptoms and the other half showing no symptoms at all. The population most affected were those over the age of 70, and as of March 14 2020 a total of seven passengers have died – all over the age of 70 – bringing the fatality rate in those infected to about 1%. While this isn’t as high as the 3.4% fatality rate that is being reported for COVID-19, it is about 10 times higher than seasonal influenza. One big concern is that COVID-19 is significantly more contagious than influenza, and so we’re likely going to see a very large spike in the number of infected people – particularly as testing becomes more available. It’s also important to note that COVID-19 is targeting people with pre-existing health issues, and for patients over the age of 70 in poor health the fatality rate may be as high as 8-15%.

What can we do to prevent coronavirus?

Like all other infectious diseases, the most important factor to prevent the spread of coronavirus is proper hygiene. It appears that COVID-19 is spread from infected persons via respiratory droplets and other bodily secretions, including mucus, saliva or feces, whether or not they have symptoms. These viral particles are then introduced into the body by penetrating mucus membranes and other exposed surfaces including the eyes, nose, and mouth. Thus to prevent exposure, one of the best things to do is to wash your hands with warm soapy water on a regular basis, and avoid touching the face or any other exposed body parts with unclean hands. The reason why masks may not be effective to stop the spread of coronavirus is because in taking the masks on and off, or if they are being reused, we may be reinfecting ourselves. Apart from proper hygiene, the practice of social distancing is recommended, making sure to keep at least 3-5 feet away from others, using the Asian-style bow, Indian-style folded hands, or touching one’s heart instead of shaking hands, hugging or kissing. Likewise it’s important during this time to avoid large crowds and busy places, and if you display any symptoms, to stay at home until you’re better. If you are around others, make sure to wear a mask to avoid spreading infectious viral particles.

How can we treat coronavirus?

While I believe Western medicine has a good handle on how to limit the spread of coronavirus, when it comes to treatment there are precious few options available, and this is where I believe that traditional systems of medicines have a lot to offer. Given that this virus appears to be targeting mostly older and immunocompromised people, as well as those suffering from comorbidities, the best thing you can do to prevent serious illness is to get healthy by following a proper diet and lifestyle (e.g. stop smoking, exercising), making sure to have access to clean air, water, and plenty of sunshine to replenish vitamin D3 levels. In all systems of traditional medicine the primary factor underlying seasonal illness is the presence of congestion, i.e. kapha/ama, phlegm/dampness, canker, etc. Therefore, it is important to take measures to prevent the accumulation of this congestive factors, and avoid any habit that produces an increase in mucus, causing the coating on the tongue to become thicker, or weakens the appetite. The best foods to eat during this time are those which are warm, soupy, light, and not too greasy, e.g. soup, kitchari, steamed vegetables, etc. Several years ago I wrote a rather extensive piece on dealing with cold and flu season; if you haven’t seen it, I suggest checking it out.

For most people, infection with the coronavirus is limited to an upper respiratory infection, causing symptoms such as runny nose, nasal congestion, and sore throat, often accompanied by some degree of bodily fever, body ache, and sometimes a dry cough. While unpleasant and uncomfortable, nothing about these symptoms is dangerous, as they represent first-line defense mechanisms the body uses to inhibit viral infiltration and replication. The real danger is when the infection descends down into the lungs causing inflammation and secondary infection, progressing from the typical cold/flu symptoms to pneumonia. In most cases this is caused because the patient aspirates (inhales) their own infected nasal secretions. Thus one of the more effective measures to inhibit this is a combination of inhalant therapies and using specialized techniques such as nasya. Inhalant therapies can be both active and passive in nature: inhaling steam medicated with essential oils such as lavender, eucalyptus, and spruce, and using bedside humidifiers at night.

To inhibit auto-infection from the nose, nasya is a fantastic technique that makes use of a medicated oil dropped into the nose to gently irritate, stimulate, and decongest the nasal and sinus mucosa, thinning the mucosal secretions, which are then expectorated from the mouth. For this purpose, a medicated oil can be made with decongesting herbs, as per the following formula:

- 2 parts bayberry

- 2 parts neem

- 2 parts mullein

- 2 parts ginger

- 2 parts licorice

Make a decoction of the herbs using one part cut/sifted herb (by weight), to four parts sesame oil (by volume), to sixteen parts water (by volume), and reduce down to four parts oil. You can test for it being ready by wetting a cotton wick in the oil, and setting this alight. If the flame burns without a crackling sound, it is done. If not, the preparation should be cooked a little longer. After it’s ready, strain through some linen or cheesecloth to filter out the herb material. If this is too difficult or time-consuming, other ready-made nasya formulations can be used such as Anu taila or Shadbindhu taila. When using any medicated oil for nasya, the general rule is to use 2-3 drops instilled into each nostril, twice daily before eating, making sure to expectorate any oil or mucus that comes to the mouth, and follow application by breathing practices such as nadi shodhana (anulom-viloma).

Coronavirus and pneumonia

If the coronavirus infection does extend down into the lower respiratory tract, it can result in pneumonia, an inflammatory condition of the lung that primarily affects the lung parenchyma including the alveolar spaces and interstitial tissues. Typical symptoms of pneumonia include chronic cough (both productive and non-productive), fever, chills, dyspnea, tachypnea, and confusion. More severe signs and symptoms include vomiting, fluctuating body temperature, blue-tinged skin (cyanosis), and convulsions. Elderly patients may also present with disorientation as the most prominent sign.

Risk factors for pneumonia include pre-existing lung problems such as chronic bronchitis, asthma, emphysema, and cystic fibrosis, as well as an impaired cough reflex (e.g. from stroke), GERD (from PPIs), diabetes, heart disease, chronic liver disease (e.g. alcoholism), chronic kidney disease, immunodeficiency, and chronic periodontitis. Pneumonia can also be acquired in a hospital setting, and is particularly common among those using mechanical ventilation by endotracheal intubation. Colloquially referred to as the “old man’s friend” pneumonia is a leading cause of death in the aged as well as in those suffering from chronic illness. Pneumonia is also more prevalent in those living in poverty. In such communities it is a leading cause of death in children, caused by poor nutrition, improper hygiene, over-crowding, and a lack of access to proper health care.

The word “pneumonia” derives from the ancient Greek word pneúmōn (“lung”), originally described by the ancient physician Hippocrates, who described in his writings how pneumonia often occurs as an epidemic illness, associating the disease with seasonal changes and in particular the influence of cold weather, which causes phlegm to accumulate in the head and then seep down into the chest. This concept of pestilence as a causative factor was explored further by the Roman physician Claudius Galen who formulated the concept of miasma, a form of air pollution caused by noxious fumes that emanate from putrid materials, which enter into the body through the lungs and skin. It is perhaps no surprise then, that many Chinese patients have succumbed to COVID-19 due to very poor air quality, compounded by the common practice of cigarette smoking.

In Ayurveda, pneumonia can be equated with a condition called uroghata, which refers to a “pain in the chest,” described in the Sushruta samhita (Uttarasthana 24:13) as a result of the neglected care of pratishyaya, or the common cold. Uroghata is of four types: one each relating to one of the dosha(s), and the fourth which is a combination of all three (sannipattaja). The primary treatment consists of specific measures to resolve the signs and symptoms along with general measures to balance the affected dosha(s).

In Chinese medicine, infectious pneumonia is a febrile disorder caused by extrinsic factors (i.e. Six Evils) attacking the Lungs, usually Wind-Heat, resulting in a Phlegm-Heat condition of the Lungs. In cases where the qi and yin of the Lungs is deficient, such as in the elderly or in those suffering from chronic disease, the Lungs cannot properly expel the Phlegm, and hence the condition stagnates and becomes a serious disorder. Here the primary approach used is to clear Heat, detoxify and resolve Phlegm, and promote the descent of the Lung qi. Where the qi and yin of the Lungs is found to be deficient, specific measures are taken to replenish qi and moisten yin, while ensuring that the excess Phlegm is properly dispelled.

In many respects the etiology of pneumonia is the same as it is for bronchitis, and thus many of the same holistic measures used for bronchitis apply in the treatment of pneumonia. In particular, it’s important to remember that most cases of pneumonia are a form of autoinfection, and hence ensuring the health of the nasopharyngeal microbiome is key to treatment and prevention: including diet and hygienic measures such as nasya and proper oral care, i.e. in Ayurveda, “tongue-scraping” (jihwanirlekhana), “cleaning the teeth” (dantadhavana), “oil-pulling” (gandusha), and “gargling” (kavalagraha).

The following is a collection of tactics used to address pneumonia and deal with both the underlying factors, the source of infection, and the specific signs and symptoms of the patient. Not every herb or tactic described below will necessarily be used; rather, each tactic should be chosen as part of an overall strategy to address the specific signs and symptoms presented by each patient.

1. Alleviate cough and pain, ensure proper respiration

There are a variety of tactics used to address cough and relieve the pain and discomfort of bronchospasm, including mucolytic expectorants, stimulant expectorants, astringent expectorants, respiratory antispasmodics, and respiratory demulcents. Reports suggest that with COVID-19 there is a greater tendency to experience more of a dry cough with difficulty breathing, suggesting that these cases may require a greater emphasis on respiratory demulcents and antispasmodics. However, given that each case may present with its own unique pattern let’s review review each group to alleviate cough and ensure proper breathing. Bear in mind, however, that many herbs display multiple properties, and just because I have placed one herb in a certain category it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have other properties too.

Mucolytic expectorants

Mucolytic expectorants are used to decrease viscosity of mucus secretions (kapha, Wind-Cold, Spleen yang deficiency). Examples include ginger (Zingiber officinalis rhizome), cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum fruit), garlic (Allium sativum bulb), aniseed (Pimpinella anisum seed), cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanica bark), angelica (Angelica archangelica root), cayenne (Capsicum annuum fruit), prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum bark), (Inula helenium root), horseradish (Armoracia sativa root), pippali (Piper longum fruit), kartakashringi (Pistacia intergerrima insect gall), cang er zhi (Xanthium sibiricum), zhi ban xia (Pinellia ternata prepared rhizome), and chen pi (Citrus reticulata peel). Mucolytic expectorants are used with caution in symptoms of heat (pitta).

Stimulant expectorants

Stimulant expectorants are used in highly congested conditions with a thick profuse catarrh (kapha, Phlegm). Examples include (Viola tricolor herb), cowslip (Primula vera herb), daisy (Bellis perrenis herb), myrrh (Commiphora myrrha resin), balm of Gilead (Populus trichocarpa leaf bud), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara leaf), gumweed (Grindelia spp. herb), marijuana (Cannabis indica/sativa flower), and kantakari (Solanum xanthocarpum herb). Stimulant expectorants are used with caution in weak/dry lungs (vata) and active inflammation (pitta).

Astringent expectorants

Astringent expectorants are used to check mucus production and reduce active inflammation (pitta-kapha, Wind-Heat, Phlegm-Heat). Examples include vasaka (Justicia adhatoda leaf), mullein (Verbascum thapsus leaf), goldenrod (Solidago canadensis herb), sage (Salvia officinalis herb), neem (Azadirachta indica leaf), bhunimba (Andrographis paniculata herb), duralambha (Fragonia cretica herb), sapistan (Cordia latifolia fruit), haridra (Curcuma longa rhizome), and huang qin (Scutellaria baicalensis root). Astringent expectorants are possibly contraindicated with symptoms of dryness (vata).

Respiratory antispasmodics

Respiratory antispasmodics are used to relieve spasmodic coughing and relax respiratory response. Examples include thyme (Thymus vulgaris herb), hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis herb), wild cherry (Prunus virginiana bark), vasaka (Justicia adhatoda leaf), mullein (Verbascum thapsus seed), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara herb), gumweed (Grindelia spp. herb), pleurisy root (Asclepius tuberosa root), lobelia (Lobelia inflata herb), eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus root), western skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus root), sundew (Drosera rotundifolia herb), bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis root), jimsonweed (Datura leaf/root), ma huang (Ephedra sinica herb), khella (Ammi visnaga leaf/seed), wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa root), and opium poppy (Papaver somniferum immature capsule). Respiratory antispasmodics are only used where there is spasmodic coughing, and some of these herbs such as ma huang should be avoided in cardiovascular issues such as hypertension.

Respiratory demulcents

Respiratory demulcents are to soothe inflammation and dryness (pitta-vata, Lung yin deficiency). Examples include marshmallow (Althaea officinalis root), slippery elm (Ulmus fulva inner bark), Irish moss (Chondrus crispus), licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra root), plantain (Plantago spp. herb), selfheal (Prunella vulgaris leaf), St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum flower), chickweed (Stellaria media herb), shatavari (Asparagus racemosa root), mai men dong (Ophiopogon japonicus root), tian men dong (Asparagus cochinchinensis root), yin chai hu (Stellaria dichotoma root), and sapistan (Cordia latifolia fruit). Respiratory demulcents are avoided with symptoms of wet/cold (kapha, Wind-Cold, Phlegm-Cold).

2. Topical measures for cough and pneumonia

Besides internal therapies and previously mentioned measures such as steam inhalation and nasya, there are a number of topical therapies that be used to treat pneumonia and alleviate chest congestion. These are applied over the chest, throat, and back as a plaster or liniment, and include examples such as mustard (Brassica nigra seed plaster), kafoori (Cinnamomum camphora leaf balm), cayenne (Capsicum annuum fruit liniment or oil), and balsam fir (Abies balsamea oleo-resin liniment, turpentine). Mustard seed is a time-honored folk remedy that is quite effective. In this case the seeds are ground into a little paste with water, and the chest is covered with a piece of wax paper. The mustard seed paste is then applied over the chest and covered with a piece of wax paper, and then this is covered with a towel. The paste is allowed to sit on the chest for 15-20 minutes until the skin becomes reddened and hot, after which it is then gently removed. The mustard seed contains antimicrobial compounds that penetrate directly into lung tissue, and the local vasodilation of the skin helps to pull blood and congestion away from the lung parenchyma, alleviating cough. If such remedies aren’t easily available, even something like Tiger Balm® or Vicks® vaporub® will be helpful.

3. Treat infection and restore the microbiome

While addressing respiratory symptoms is a big part of treating pneumonia, it’s also important to include a tactic to resolve the underlying infection and re-establish a healthy microbiome. Some of these measures include the use of herbs with antiviral, antibacterial, and anti fungal properties, as well as pre/probiotic supplements and foods.

- Antiviral herbs, as a first-line treatment for COVID-19, include St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum flower), osha (Ligusticum porter/canbyi root), biscuit root (Lomatium dissectum/nudicaule root), bhunimba (Andrographis paniculata herb), ban lan gen (Isatis tinctoria root), and yu xing cao (Houttuynia cordata herb).

- Antibacterial herbs, to treat secondary infection, include goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis rhizome/root), purple coneflower (Echinacea angustifolia root), wild indigo (Baptisia tinctoria root), garlic (Allium sativum bulb), myrrh (Commiphora myrrha), neem (Azadirachta indica leaf), bhunimba (Andrographis paniculata herb), haridra (Curcuma longa rhizome), huang lian (Coptis chinense root/rhizome), lian qiao (Forsythia suspens flower), jin yin hua (Lonicera japonica flower), ban lan gen (Isatis tinctoria root), and huang qin (Scutellaria baicalensis root).

- Prebiotics, e.g. FODMAP-containing foods, chicory root, beet root, fructo-oligosaccharides (e.g. inulin)

- Probiotics, e.g. Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium etc., live-culture lactofermented foods

4. Modulate and support the immune system

Beyond dealing with lung issues and addressing infection, it is also important to take measures to support the immune system. This may include measures to either boost, modulate, or down-regulate immune responses depending on the signs and symptoms and case history of the patient. While the cytokine storm observed in H1N1 and H5N1 influenza doesn’t seem to be a factor in COVID-19, it may be important to down-regulate inflammation, using cytokine storm inhibitors such as licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra root), boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum herb), huang qin (Scutellaria baicalensis root), elderflower (Sambucus nigra flower), jin yin hua (Lonicera japonica flower), and xi yang shen (Panax quinquefolium root).

Given that COVID-19 seems to be more lethal in elderly and immunocompromised patients, herbs with adaptogenic and immunomodulating properties that help build and enhance the vital reserve (i.e. ojas, qi) are likely indicated, including reishi (Ganoderma lucidum fruiting body), maitake (Grifola frondosa fruiting body), huang qi (Astragalus membranaceus), amalaki (Phyllanthus emblica fruit), and wu wei zi (Schizandra chinense fruit).

A class of herbs referred to as respiratory restoratives are also indicated in this case, including herbs such as bibhitaki (Terminalia belirica fruit pulp), punarnava (Boerhavia diffusa root), ashwagandha (Withania somnifera root), ren shen (Panax ginseng root), American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium root), dang shen (Codonopsis pilosula), and fu ling (Poria cocos fruiting body).

Additional immunosupportive nutrients include vitamin A (25,000 IU daily), vitamin B complex (50 mg daily), vitamin C (to bowel tolerance), vitamin D3 (5000 IU daily), vitamin E (400 IU daily), and zinc (50 mg daily).

5. Useful formulas in cold, cough, and pneumonia.

While it is very possible to create a custom formula from some of the herbs described above, there are a number of standard formulas drawn from Ayurveda, Chinese medicine, and Unani medicine that would likely be of great help in treating COVID-19 pneumonia. This is not an exhaustive review of every single formula, but some key formulas used in each tradition, and are represented to provide some examples of how some of herbs already described can be used together.

Ayurveda formula: Chaturdasangha churna

Contains equal parts katphala (Myrica nagi bark), nilotpala (Iris nepalensis flower), karkatashringi (Pistacia intergerrima insect gall), pippali (Piper longum fruit), maricha (Piper nigrum fruit), shunthi (Zingiber officinalis rhizome), duralambha (Fragonia cretica herb), krisnajiraka (Nigella sativa seed), musta (Cyperus rotundus tuber/rhizome), talisha (Rhododendron stesum leaf), twak (Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark), patra (Cinnamomum tamala leaf), sthula ela (Amomum subulatum fruit), and nagakeshara (Mesua ferrea seed).

Taken with honey as an anupana, Chaturdasangha churna is used as a general formula for kasa (cough), shwasa (asthma), uroghata (pneumonia), and parswashula (pleurisy).

Rx: powder, 1-3 g bid-tid

Ayurveda formula: Mrgamadasava

This formula is made from a distillation of a fermented preparation called Mrtasanjivani sura which contains 45 different ingredients, that is mixed with latakasturi (Hibiscus abelmoschus seed), and other herbs such as maricha (Piper nigrum seed), lavanga (Syzigium aromaticum flower bud), jatiphala (Myristica fragrans seed), pippali (Piper longum fruit), and twak (Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark).

Mrgamadasava is a very spicy and stimulating formula that is effective for overcoming dampness and congestion, and has the power to restore breathing in very difficult cases. Mrgamadasava is used for uroghata (pneumonia), vishuchika (painful gastroenteritis), hikka (hiccough), sannipataja jwara (tridosha fever).

Rx: liquid extract, 10-20 gtt bid-tid

Chinese medicine formula: Yin Qiao San (Honeysuckle and Forsythia Powder)

This formula contains jin yin hua (Lonicera japonica flower – 15 g), lian qiao (Forsythia suspens flower – 15 g), jie geng (Platycodon grandiflorum root – 6 g), niu bang zi (Arctium lappa seed – 12 g), bo he (Mentha haplocalyx herb – 6 g), dan dou chi (Glycine max fermented fruit – 6 g), jing jie sui (Schizonepeta tenuifolia herb – 9 g), dan zhu ye (Lophatherum gracile stem – 6 g), and gan cao (Glycyrrhiza uralensis root).

In Chinese medicine Yin Qiao San is used as a first-line remedy to disperse Wind-Heat, clear Heat, and resolve toxicity. While not specifically used for pneumonia, this formula is helpful to address the underlying infection and fever.

Rx: powder, 9 g of this powder is taken with a mild decoction of xian lu gen (Phragmites communis recently dried rhizome – 30 g).

Chinese medicine formula: Ma Xing Shi Gan Tang (Ephedra, Apricot Kernel, Gypsum and Licorice Decoction)

This formula contains ma huang (Ephedra sinica herb – 12 g), xing ren (Armeniaca amarum seed – 12 g), shi gao (gypsum 40 g), and gan cao (Glycyrrhiza uralensis root – 10 g). Currently, the administration overseeing the practice of Traditional Chinese Medicine in China suggests a modified form of Ma Xing Shi Gan Tang for COVID-19 also containing huo xiang (Agastache rugosa herb – 15 g), pei lan (Eupatorium fortunei – 15 g), cang zhu (Atractylodes lancea – 15 g), sha ren (Amomum villosum – 10 g), ban lan gen (Isatis tinctoria herb – 20 g), shen qu (Massa fermentata – 30 g), sang bai pi (Morus alba – 15 g), and pipa ye (Eriobotrya japonica – 15 g).**

Both the original and modified forms of Ma Xing Shi Gan Tang clears Heat and resolves Phlegm, used to treat cough, difficulty breathing, weak appetite, fatigue, thirst, and fever. Given that ma huang has adrenergic and vasoconstrictive properties, it is probably wise to avoid this particular herb in patients that present with hypertension.

Rx: decoction, 200 mL bid-tid

Unani medicine formula: Laooq-e-Sapistan

This is a confection that contains sapistan (Cordia latifolia fruit) and unnab (Zizyphus vulgaris fruit) as the primary ingredients, with smaller amounts of koknar (Papaver somniferum immature seed capsule) as an antitussive, and other herbs including asl-ul-soos (Glycyrrhiza glabra root), parsiyaoshan (Adiantum capillus veneris rhizome), tukhm-e-khatmi (Althaea officinalis seed), tukhm-e-khubbazi (Malva sylvestris seed), and behidana (Cydonia oblonga seed). These herbs are decocted and then mixed with qand safaid (sugar), and cooked down to the consistency of a syrup, during which are added smaller amounts of sheera-maghz-e-badam (Prunus amygdalus seed), sheera-e-tukhm-e-khashkhash (Papaver somniferum seed), katira (Cochlospermum religiosum gum), samagh-e-arabi (Acacia arabica gum), and rubb-us-soos (Glycyrrhiza glabra root extract). The primary herb in the formula called sapistan fruit has a cooling anti-inflammatory effect, used as an expectorant and antitussive agent, and has both astringent and demulcent properties. The formula Laooq-e-Sapistan is used for nazla (catarrh), zukam (coryza), sual-e-muzmin (chronic cough), and anaf-ul-anzah (influenza).

Western herbal medicine formula: Cough Powder

First mentioned in Benjamen Colby’s Guide To Health (1846), this cough powder contains one part each finely sieved powders of cayenne (Capsicum annuum fruit), lobelia (Lobelia inflata herb), skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus root), wake robin (Trillium erectum root), valerian (Valeriana officinalis root), and prickly ash (Zanthoxylum americanum bark), along with two parts slippery elm (Ulmus fulva inner bark). Of this mixture, the dose is 1/2 to 1 tsp of the powder mixed hot water, given every 2-3 hours.

Western herbal medicine formula: Winter Solstice Cough/Cold Syrup

This formula was developed by herbalist Michael Moore, and is prepared from tinctures and mixed with an equal portion of Monarda or Manuka honey to create a syrup. Vegetable glycerin can also be included as a portion of the honey used in the final preparation. The Winter Solstice Cough/Cold Syrup contains four parts wild cherry (Prunus virginicus bark) tincture, and three part each tinctures of white pine (Pinus strobus bark), osha (Ligusticum porter/canbyi root) tincture, elecampane (Inula racemosa root) tincture, balsamroot (Balsamorhiza sagittata root) tincture, sweetroot (Osmorhiza occidentalis root) tincture, and licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra root) tincture. Of this mixture, the dose is 5-10 mL, given 3-5 times daily.

________________

** Ochs S, Avery-Garran T. 2020. Official Treatment Protocols Include Chinese Herbal Medicine Formulas for Novel Coronavirus. Available from: http://passiflora-press.com/covid-19/

Also, does one continue nasya if there are symptoms or is it discontinued?

Nasya with the formula mentioned can be continued with symptoms as long as they aren’t too congesting. Otherwise, we might try another approach.