Antibiotic resistance: a herbalist’s perspective (1)

If you have been keeping abreast of science news as of late, you might have come across a recent article published in the journal Nature, which again raises the emerging specter of antibiotic resistance. In a nutshell, antibiotic resistance describes a phenomena in which bacteria that were formerly susceptible to antibiotics are now resistant to them. Antibiotics were developed in the early 1900s, first with the development of the sulfonamides in the 1930s, the penicillins in the 1940s, shortly followed by an ever-growing list of antibiotics, including the tetracyclines, glycopeptides (e.g. vancomycin), metronidazole, cephalosporins (e.g. cefadroxil), and fluoroquinolones (e.g. ciprofloxacin).

The development of antibiotics has been hailed as one of the great achievements of modern medicine, but as a herbalist, I have always found the boastful crowing of advocates rather high-pitched, particularly as how I have treated many cases of serious infection using methods that predate Western medicine by thousands of years. None of my three children (aged 19, 18 and 12) have ever taken antibiotics – not because I am totally opposed to them – but because I have never needed to use them. But when I compare my experience to the norm, in which the average American child has received up to 20 courses of antibiotics before the age of 18, it is clear that my experience as a parent is rather unusual.

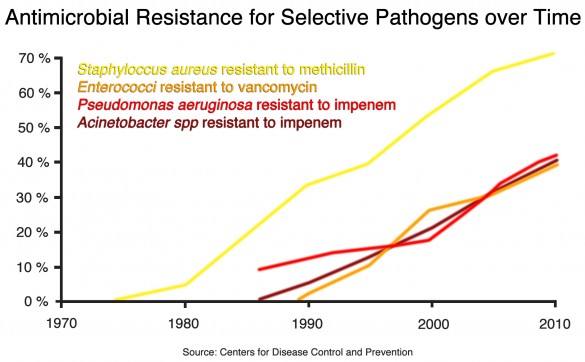

According to the WHO, we are now living in a “post-antibiotic” era in which even the most potent of antibiotics such as the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin, originally developed as a treatment for penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is now demonstrating signs of failure. All over the world, but particularly in developing countries such as India, China and Brazil, the wide-spread use of antibiotics in both medicine and agriculture coupled with poor sanitation has fueled the evolution of antibiotic resistant organisms. According to the article in Nature, “up to 95% of adults in India and Pakistan carry bacteria that are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics,” a class of drug that accounts for more than half of all commercially available antibiotics.

When I lived in India several years ago, almost any medication I wanted was available from local pharmacies without a prescription, and in a country that aspires to reflect the Western lifestyle, medications such as antibiotics were held in clear preference to traditional methods of infection control. Educated moms with sick babies didn’t want to use ‘old’ traditional remedies – they wanted the ‘best’ that medicine had to offer, along with everything else the modern world promises them. Apart from the easy availability and overuse of antibiotics, the other reason why developing countries such as India and Pakistan are being hit so hard by antibiotic resistance is due to the contamination of public drinking water with sewage and waste water. Combined with the sheer number of people living in close quarters throughout the developing world, the failure to ensure the proper treatment of sewage and drinking water has dramatically sped up the evolutionary development of bacteria. But while it is easy to point to the third world and blame the victims for causing their own problem, we need to develop a broader perspective, and question if the problem isn’t the entire concept of an ‘antibiotic’ itself.

It is an essential fact of biology that all beings on earth, whether sedentary plants or the mobile animals, that each owes their origin and ongoing existence to bacteria. Called the prokaryotes, bacteria are the simplest living cells on earth and can be found in almost every environment, including the deep-sea thermal vents thousands of meters below the surface of the ocean. These deep sea vents are thought not just as the origin of life of earth, but similar to the appendix of the human colon, serve as a repository of life if there is ever a major disaster on the earth’s surface (or in the case of your appendix, the destruction of your gut flora). In contrast, cells that comprise the tissues of both plants and animals are called eukaryotes: much larger cellular structures that show evidence of endosymbiotic evolution, in which smaller prokaryotes combined billions of years ago to create a kind of super-organism.

We see evidence of endosymbiotic evolution in our own cells, such as the semi-autonomous mitochondria that provide our bodies with energy, which have their own separate set of DNA, enzymes and transport systems. Further evidence of our deep kinship with bacteria is marked by the presence of commensal “probiotic” bacteria that play a key role in maintaining a huge array physiological functions, from the assimilation of nutrients to the regulation of the immune system. In a similar fashion, all living organisms on earth owe their origin and function to bacteria, and it is fundamentally wrong that we have decided to take an adversarial position against them. Evidence of this misconception is found in the word ‘antibiotic’ itself, which simply means ‘anti-life.’ The use of antibiotics is predicated upon a 20th century scientific notion that is firmly rooted in a paternalist mindset that human beings are somehow separate from the rest of life. It is this “fact” alone that qualifies us to employ a mandate which is “anti-life”, and simultaneous with the loss of more than half of the earth’s species and forests over the last 40 years, serves as moral justification to commit unadulterated microcide on an enormous scale.

Today, antibiotic compounds are not just abused as a medicine, they have found their way into every element of our life. Triclosan, for example, is but one chlorinated antibiotic compound found in over 1600 retail products in North America, including soaps, deodorants, cosmetics, lotions, shampoos, toothpastes, mouthwashes, OTC and prescription medications, as well as sham natural products such as grapefruit seed extract. Research has shown that exposure to triclosan is associated with food allergy, endocrine dysfunction, and cancer, and is now so widespread in the environment that it’s been found in the bile of fish living downstream from wastewater processing facilities, as well as in human breastmilk (1).

The use of antibiotics by humans, however, only accounts for a fraction of their total use. Recent estimates suggest that more than 70% of all antibiotics produced are used for non-therapeutic purposes (i.e. ‘preventative’) in food animals (2). The residues of over 12 different classes of antibiotics are found in our food, and what we don’t ingest the remainder is released in massive pools effluent that seeps into the water table, and poisons the local environment. In the end, the assumption of separateness that predicates the use of antibiotics is dead wrong, and a failure to fully grasp not just the technical issue of antibiotic resistance, but its philosophical underpinnings, means that this issue will continue to get worse.

When antibiotics were first developed in the early part of 20th century, scientists unwittingly initiated an arms race with bacteria. We didn’t know that unrelated bacteria can easily share genetic information with other bacteria, and thus if even one bacterium survived exposure to an antibiotic, it could share this “experience” with other bacteria to provide the genetic information that allows for the development of antibiotic resistance.

Likewise, when we first isolated antibiotic compounds from different types of fungi, such as penicillin from Penicillium chrysogenum, we didn’t (and mostly still don’t) appreciate how isolated chemicals such as penicillin work synergistically with other natural compounds produced by the fungus to exert a stronger, more complex effect to prevent resistance (2, 3). Essentially, what we did is pluck one “elite” compound from an army of antimicrobial compounds found in this fungus, and then use only it to wage our bacterial battles. Translating the analogy to human terms, it would be like a general using only his special OPs to fight a conventional war, with the same unchanging method of strategy and tactics. And just like in every other military scenario where the larger aggressor maintained such arrogance, from the American Revolutionary War to Vietnam, those who seek to vanquish eventually become vanquished themselves.

If the cause of antibiotic resistance is ignorance, it is that we failed to account for the complexity of life. When any of us starts out to learn something, we often see things in black or white. This is has been as true of science as it is for each of us. People with loud opinions, speaking in black and white terms, only demonstrate their lack of sophistication: for them, the appeal of their argument is in its simplicity. The knowledge we can have confidence in, however, is rarely so clear, and true experts are those who realize just how little they actually know. Thus, if we are honest with ourselves, we need to admit that nothing is black or white but instead shades of grey, where “facts” are really just opinions with a long shelf life.

This is has been observed in medicine, that what is perceived to be true has an average half-life of 45 years before it is superseded, often radically, by a completely different perspective. In science, the dynamics of this reality should give rise to the “precautionary principle”, a fancy sounding ethic based upon the time honored aphorism of “better safe than sorry”. The problem is, of course, that the precautionary principle is directly opposed to the motives of greed; and because our medical system as well as most science and technology depends on capital generation, the precautionary principle precludes success. Hence, another cause of antibiotic resistance is not just ignorance, but also our lust for financial and material gain. Add to this the extreme aversion of “germs” that has been marketed and instilled into the population over the last 75 years, I am reminded of the three poisons of Buddhism: ignorance (avidyā), greed (rāga), and aversion (dveṣa). It is from these three conditions that the specter of antibiotic resistance arises, and it is only through the proper comprehension of these factors that can we begin to make any significant headway on this problem.

In part two of this post, I’ll describe some of the ways we might be able to restore balance, delving into a little bit of herbal biochemistry, and some time-honored herbs that can be used for antibiotic resistant bacteria. In the meantime, please write in with your thoughts or experiences on the issue of antibiotic use.