This FAQ was developed in response to the many inquiries we receive with regard to the educational opportunities we offer at the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine. If you have a question, please take a look here first. If you can’t find a response to your question, please use our contact page to send us a message!

To see the answers, please click on the plus sign (‘+’) next to the question. To close the question, click on the minus sign (‘-‘).

Contents

- General Questions

- Questions about our Distance Learning Programs

- Questions about the Mentorship Program

- Questions about credentials and certification

- Questions about cost and payment

General Questions

As for where to start with us, both Food As Medicine and Inside Ayurveda are great places to start learning, especially if you want to get going right away! If the online format works for you, and you’re a real newbie, I think herbmentor.com is a great place to start. But if you want to dig deeper, we’re like the next step. However, not every program is going to suit every person. Once again, a good place to start looking is on the American Herbalists Guild school listing.

Questions about our Distance Learning Programs

As for our other two courses, Food As Medicine and Phytomedica, the first of these was originally published as a book of the same name, written for patients and consumers that were interested in the therapeutic properties of food. The book, however, is filled with information, and although it approaches the reader at a beginner level, it also discusses many technical issues that are better introduced and discussed as part of a course. The Food As Medicine Online Learning Program is thus for anyone interested in the therapeutic properties of food, and is designed to provide students with a sophisticated knowledge of food that can be used for personal use and clinical practice.

The third component of our distance-learning triumvirate is Phytomedica. This 28 class program is an integrated approach to the use of nutrition, herbal medicine, and preventative medicine in clinical practice, drawing upon several traditions and aspects of medicine, including Ayurveda, Chinese medicine, and clinical nutrition. Although it is optional, it is highly recommended that the other two distance-learning programs, i.e. Inside Ayurveda and Food As Medicine, are completed before Phytomedica is begun.

Questions about the Mentorship Program

In contrast, the modern education system that most of us grew up with owes its origin and structure to a model developed in Germany during the 18th century, called the Prussian model of education. In many ways, this Prussian model unintentionally reinforces many aspects of 18th century Germanic culture that are at odds with today’s social values, such as income and gender equality. For example, there was a high degree of social stratification in 18th century Germany, with a hierarchy of wealthy landowners and aristocrats, and an underclass of soldiers and peasants that served them. The classroom environment within the Prussian model of education thus reflects this hierarchy, with students as the ‘serfs’ or ‘soldiers’, seated in organized rows, stripped of their autonomy, their attention focused towards the front of the room, submitting to the authority of the teacher, or ‘king’. The 18th century also the period during which the common people formerly self-employed in cottage industries, passing skills on to their children, were forced to work as employees inside dirty factories in terrible conditions, under constant duress and surveillance. In this way, the modern education system employs the same kind of factory model, with students herded into what are often fierce-looking or otherwise imposing institutional buildings, forced to huddle and move about from room to room, always under surveillance, always under the implicit threat of some kind of punitive measure if they don’t fall in line. The 18th century was also the beginning of the Age of Enlightenment, and with the printing press making it so much easier to transmit information, education quickly became reliant upon theoretical, or ‘book’ knowledge, whereas practical ‘everyday’ knowledge was scorned and consigned to the realm of second class citizens. A “well-read” and “literate” man was an “intelligent” man, regardless of whether or not he had any practical experience about which he read; or indeed, if his “educated” opinions on the subject were even true. In this way, the British were able to justify the suppression of Indian culture during the colonial period, by suggesting that the “educated” British had themselves given rise to Indian culture many thousands of years before. Likewise, in 18th century medicine, Western doctors were taught to eschew the benefits of herbal medicines, and instead employ high doses of mercury or drain patients of blood in the treatment of almost any disease, all based on the idea that these methods would somehow be helpful. In this latter example, the routine poisoning and bleeding of patients continued right up until the late 18th century, the evidence of which remains preserved in the title of a medical journal founded in 1823 called The Lancet, named after the sharp knife used open the patient’s veins for bleeding.

This dissociative process, wherein humans create and maintain structures of logic that separate ourselves from the nature of reality, emanates from a broader cultural shift in European society that coincided with industrialization and modernization. In less than two centuries, Europe transformed from being a largely agricultural, faith-based society, to one that was increasingly industrialized, and mechanistic in its outlook. Thus, as the modern education system developed, the concept of the immutable soul of the student was supplanted by an industrial model, wherein the ultimate goal of education was to meet the needs of a rapacious machine, i.e. the ‘economy’, rather than instilling the values of goodness. Today, even the highest academic institutions continue to use this anachronistic model of education, all based on a factory model of herding large groups of students into room after room every couple hours, filling their heads with a diverse array of disjointed information, and then testing them periodically to see how well they can remember it. This type of education might work well if your life goal is middle management in a factory, but if you want to apply yourself skillfully in this world, and do something that truly matters, you will find this type of education is woefully inadequate.

To apply any knowledge skillfully requires a great deal of time and practice, which is why working with experienced people is the fastest route to true knowledge. In this sense, “true” knowledge is practical knowledge, borne from decades and even generations of observing and bearing witness to the real time application of knowledge. It is the difference between studying how to drive a car in a classroom or a simulator, versus actually taking the car on to the road with an experienced driving instructor. True knowledge is the stuff that cannot be taught as a strict pedagogy. It’s been said before and it remains true today: nature does not write textbooks. True knowledge cannot be taught in an abstract, dissociated fashion. To learn how to do anything well, one must be taught personally how do it, or otherwise spend a great deal of time acquiring that knowledge on their own, through trial and error. Mentorship is a short-cut to a lifetime of experience.

The goal of the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine, and what makes it different from conventional academic training, is that it is designed to meet the needs of the student as best as possible. It’s not about “bums in seats” and “cramming for exams”. The Mentorship program is self-paced, multi-tiered, and modular in its approach, which allows for a great deal more convenience and flexibility for the student. The approach of immersing a student into one key subject area for weeks or months at a time is another key difference between the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine and other training programs, allowing the student to fully comprehend and apply the knowledge, rather than jumping from subject to subject over a period of several years, only developing a cursory knowledge. The entire focus of the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine program is to provide real time skills, based on the wisdom and skill of experienced practitioners, and venerated traditions. To be sure, science and academia inform our approach to knowledge, but free of corporate sponsorship, consumer products sales and government regulation, the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine has chosen to chart a path towards the development of goodness in society, with the ultimate goal of creating good practitioners.

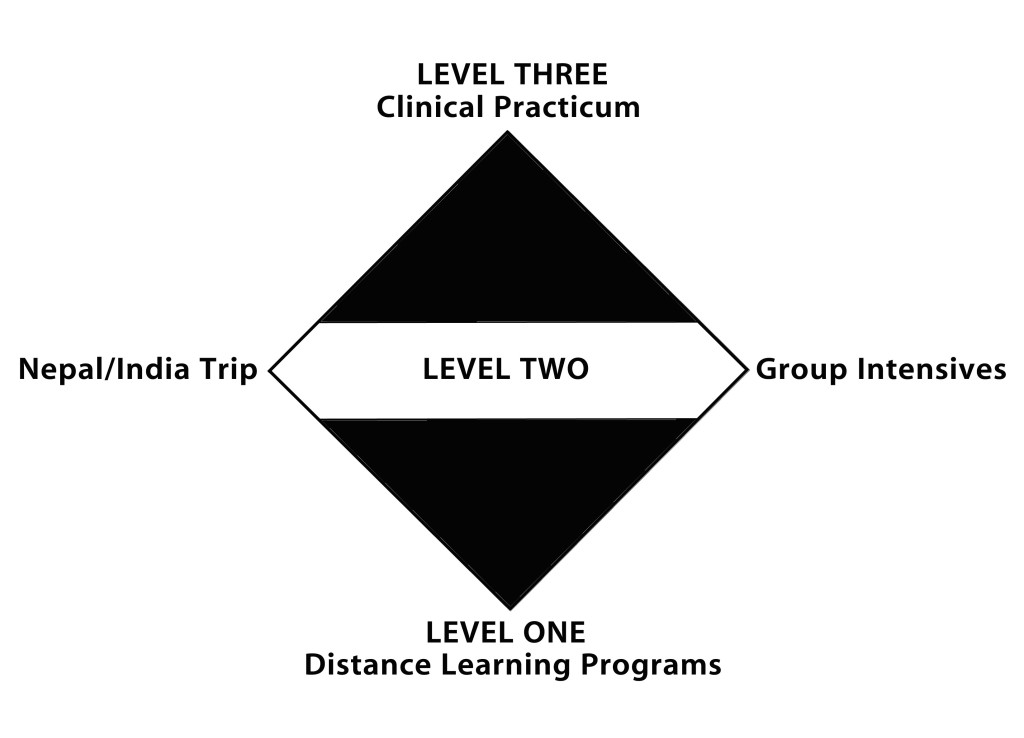

At the bottom of this diamond is the first level of training, which contains the distance learning courses, including Inside Ayurveda, Food As Medicine, and Phytomedica. Students that successfully complete these materials are then eligible to continue on to the second level. The second level is two-pronged, consisting of the Ayurveda in Nepal program and the Group Intensive Program. The prerequisite for the Nepal-India Study Program is Inside Ayurveda, whereas the prerequisites for the Group Intensive Program include all three components of Level One (i.e. Inside Ayurveda, Food As Medicine, and Phytomedica). The first Ayurveda in Nepal program will happen in early 2017, and will provide an authentic, practical grounding in Ayurveda. Following this, in the fall of 2017, we will begin to roll out the Group Intensive Program, consisting of 14 modules that address an important area of clinical work. Each one of these 14 modules will be held over a 2-3 week period, offered every 3-4 months. Thus, the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine Mentorship program allows the student to continue living and working wherever they are, and only interrupt their busy lives for these periodic intensives. When Level Two of the Mentorship program is complete, students move on to Level Three of the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine Mentorship Program, consisting of the clinical practicum. The Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine requires that students initially complete their first 50 hours of clinical training with the school, but after this, students are encouraged to complete their remaining 150 hours with other skilled clinicians that are recognized by the Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine.

Including lectures and discussions, the entire Dogwood School of Botanical Medicine Mentorship program is approximately 1400-1600 hours, not including exams, quizzes, assignments, and self-study:

• Inside Ayurveda: 110 hours

• Food As Medicine: 100 hours

• Phytomedica: 210 hours

• Ayurveda In Nepal: 200 hours (five weeks)

• Group Intensives: 600 hours (14 sessions)

• Clinical practicum: 200 hours

Please note that these are estimates, as the actual number of hours may vary from student to student, and programs and program hours are subject to change.

Questions about credentials and certification.

Questions about cost and payment