Among the great medical traditions of the world, Unani and Islamic medicine have left an indelible imprint upon the practice of healing. Unani medicine, the Arabic name for “Greek” medicine, is a heterogeneous mixture of medical practices from many different cultures. It begins, if anything can said to have a beginning, with the ancient practices of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers and Mesolithic nomads that roamed northern Africa and the Arabian peninsula, probably not too dissimilar from the modern-day Bedouins. With the advent of agriculture, this comparatively primeval system of healing was shaped over thousands of years into the highly technical medical practices of Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilization. In the sunset years of these ancient civilizations, some of these practices were kept alive by the emerging culture of Greece, most notably by the Greek scholar Hippocrates (c. 460? — 380? B.C.E.), who is thought to have based some of his approach upon Egyptian medical practices (Wallis 1996, 56).

Hippocratic medicine revolutionized health care in Greece, becoming an integral part of Greek culture and an important export to neighboring societies. It probably reached its widest audience under the military expansionism of the Macedonian emperor Alexander (c. 356 — 323 B.C.E.), who brought it as far eastward as northwest India. Greek medicine was also furthered by the great Roman physicians, such as Galen (c. 129 — 210 C.E.), and with the decline of the Roman Empire, this knowledge was, in turn, preserved and developed by the emerging Arabic empire.

Among the many notable examples of important Arabic contributors to medicine include the philosopher-scientist Ibn Sina (Avicenna, c. 980 — 1037 C.E.), whose text “Canon of Medicine” was in use by physicians all over the western and middle-eastern world for over 600 years. The Muslim advance into Europe and the campaigns of the Christian Crusades (between 1096 and 1270 C.E.) suffused European culture with the concepts and practices of the ancient Greeks, an event which later set the ground for the European Renaissance. Concurrently, with the Muslim invasions of western India in the period of time between the 12th and 15th centuries, the Islamic-influenced practices of Unani were eventually conjoined with the Greek medicine of northern India, already a millennia old since Alexander’s invasion. Unani medicine continues to be an important form of health care for much of the world’s population, drawing upon the inexhaustible origin of its history, and shaped by the philosophical tenets of the holy Qur’an.

History of the Middle East

There is very little known about the lives of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic peoples who inhabited northern Africa and the Mid East, a history which seems obscured by the enormity of the ancient agrarian civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. This obscurity is due, in part, to the lack of reliable archeological and anthropological evidence, and confounded by the reality that these ancient peoples had little interest in building lasting monuments, and kept few records of their achievements or experience. Much of what can be said of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic people of the Mid East and northern Africa is thus a general history, pieced together by evidence from all over the world.

According to the single origin theory of modern anthropology, the modern day human (Homo sapiens sapiens) originated in Africa or the Mid East about 100,000 to 200,000 years ago. The migration of this group to other parts of the world eventually superceded the older hominid populations such as the Neanderthals, and slowly began to display physical adaptations such as changes in skin and hair that mark the different races of today. Until about 35,000 years ago, the technology of our modern human ancestors does not appear to be all that different from earlier human and Neanderthal populations, with a reliance upon simple stone tools, and a diet of wild vegetation, small game animals, and scavenged flesh, as well as ocean and fresh water foods such as fish and mollusks.

Although no one is exactly sure why or how, from about 40,000 to 35,000 B.C.E. the first “behaviorally modern” human beings evolved, evidenced by an explosion of new forms of stone and bone tools, cave paintings and other artwork, plus elaborate burials and many other typically modern human behaviors. These Paleolithic (early stone age) people were hunter-gatherers like their ancestors, but their diet was comprised of an increasingly larger component of large game animals than previous hominids, supplemented by a varying diversity of wild vegetation. Mesolithic peoples evolved later by the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age about 11,500 years ago, developing precursor forms of wild plant and game management that is perhaps best represented in modern times by nomadic peoples such as the Bedouins.

Although the land is now characterized by extreme aridity, annual grasses and low shrubs once covered ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Desertification of these areas appears to be a relatively abrupt event that began to occur about 9000 years ago, corresponding with a shift in the Earth’s axis and the resulting atmospheric and vegetation feedbacks in the subtropics. This loss of habitat increased the pressure on populations of wild game, forcing some Mesolithic people towards the Tigris, Euphrates and Nile rivers, where Neolithic (later stone age) developments such as fishing, agriculture, and polished tools began to evolve. It is within these centers that highly sophisticated civilizations began to evolve, beginning with the Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia, followed by the Babylonian and Egyptian dynasties.

Mesopotamia

Very little information on the ancient medical practices of Mesopotamian civilization remains, although as Egypt derived certain aspects of their culture from Sumeria and Babylonia, we can speculate that some Mesopotamian medical practices are represented by Egyptian sources such as the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1500 B.C.E.). Egyptian medical practices may also represent those of ancient India as well, as recent anthropological evidence suggests an important link between the Sumerian civilization and the equally ancient Harrapan civilization of northwestern India.

What we known of Mesopotamian civilization is largely based upon ancient clay tablets and tablet fragments written in cuneiform. Cuneiform is a system of writing similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs, established by the Sumerians to later become the dominant system of writing in Mesopotamia for over 2000 years, even after the Sumerian language became extinct. Unfortunately, while an abundance of cuneiform tablets have survived from ancient Mesopotamia, relatively few are concerned with medical issues. The largest surviving medical treatise from ancient Mesopotamia is known as the Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognoses, consisting of 40 tablets that date back to around 1600 B.C.E. (Demand 1997). This “text” is likely a compilation of preexisting medical knowledge several centuries old, organized in a complete head-to-toe fashion, with separate subsections covering convulsive disorders, gynecology and pediatrics (Demand 1997). Although the language in which these texts are written could be considered superstitious and overly concerned with the influence of spirits and demons, recent research has shown that the poetic language otherwise demonstrates a keen diagnostic ability. Many diseases are described in parts of the diagnostic treatise, listing the features of neuropathologies, fevers, parasitic infection, venereal diseases, and skin lesions. The methods of treatment appear to be completely rational, essentially the same as modern treatments for the same condition (Demand 1997).

Medical treatment in ancient Mesopotamia appears to have been delivered by one of two practitioners: the ashipu or the asu (Demand 1997). The ashipu was a kind of shaman whose role it was to determine if an illness was caused by either supernatural or more mundane sources, such as a diseased organ. If the illness was determined to have supernatural causes, or if it was the result of some omission or sin on the part of the patient, the ashipu could provide certain spells and incantations to ameliorate these effects. The condition would be described as the influence of a particular spirit or demon, whose influence extended only to a particular organ and area of the body. The ashipu could also refer the patient to an asu, who specialized in herbal medicines, bone-setting, and surgery. Very often these two practitioners would work in a complimentary fashion, providing care in the patient’s own home. Recent excavations of the ancient temple of Gula in Iraq have revealed Gula to be an important deity of healing, and this location may have been an important center for diagnosis and treatment, similar to the latter-day Aesclepian temples of ancient Greece (Demand 1997). The sacred Tigris and Euphrates rivers also appear to be sources of healing, both spiritually and physically, perhaps in much the same way that Hindus hold the Ganges River in reverent regard.

Ancient Egypt

There is little doubt of the enormity of the influence of ancient Egyptian civilization, perhaps best represented by the enormous shadow of the pyramids at Giza, as well as the wealth of archeological and anthropological information that has been obtained through more than a century of painstaking research and excavation. Unlike the civilizations of Mesopotamia, historians have been able to put together a fairly coherent picture of the evolution of ancient Egyptian civilization, although some researchers such as John Anthony West (Serpents in the Sky: The High Wisdom of Egypt) dispute some of the tenets of modern Egyptology. Among the earliest Neolithic settlements are the Badarians of Upper Egypt (near modern-day Cairo), dating back between 5500 and 4500 B.C.E. This was followed by the larger communities of the Nagada in the fourth millennium B.C.E., a period generally regarded as the beginning of the pre-dynastic period of Egypt.

Throughout most of its pre-dynastic history, Egypt contained a large diversity of settlements that gradually became small tribal kingdoms. These kingdoms eventually merged into two loosely confederated states, one encompassing the Nile valley up to the Delta, represented by a White Crown, and the other encompassing the Delta region, represented by a Red Crown. The two kingdoms vied for power, eventually leading to the unification of Egypt in 3100 B.C.E. under the command of Menes, although which group prevailed, whether Upper or Lower Egypt, is unclear. Menes created a national government and moved the capital of Egypt to Memphis, near modern-day Cairo.

The Dynastic period of Egypt is comprised of four major epochs: the Early Period, the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom. The dynasties of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 — 2181 B.C.E.) mark the consolidation of a strong central government and the construction of the great pyramids. It was during the New Kingdom (c. 1554 B.C.E.) however that Egypt gained the reputation as a world power, with Thutmose III (c. 1490 — 1436) bringing Palestine and Syria into the Egyptian empire. At this time Thutmose III also reestablished Egyptian control over what is modern Sudan, which was a valuable source of slaves, copper, gold, ivory, and ebony. As a result of these victories, Egypt became the strongest and wealthiest nation in the Middle East.

With the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaton, c. 1367 — 1350 B.C.E.), and his insistence that the populace replace their worship of all previous deities, save Ra, with Aton, Egypt entered into a period of decline. The anger and unrest created by Akhenaton intensified after his death until King Tutankhamen (c. 1347 — 1339) restored the old state religion. The Egyptian pharaohs recovered from this decline to a degree with the reign of Seti I (c. 1303 — 1290 B.C.E.), and his son Ramses II (c. 1290 — 1224 B.C.E.), regaining the territories that had been lost after the reign of Thutmose III. After Ramses II however, increasingly bitter struggles for royal power by priests and nobles broke the country into small states, attracting foreign control over the next 700 years by Nubian, Assyrian, and Persian rulers.

In 332 B.C.E., the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great added Egypt to his empire, and in that same year, Alexander founded the city of Alexandria in the Nile delta. Under his patronage and that of the Ptolemies, Alexandria quickly became a world center for study and learning, with the famed library of Alexandria containing between 400,000 and 500,000 texts of Egyptian, Greek, and Persian knowledge. This collection was partially destroyed in a fire in 80 B.C.E., and later was completely destroyed under the reign of the shortsighted Theodosius I (c. 346 — 395 C.E.), who outlawed all non-Christian pagan practices.

Egypt remained an important center of the Byzantine Empire until the Arab invasions of the 640’s C.E., which was eventually succeeded by the Turkish Ottoman Empire in 1517 C.E.. In 1798 the French Emperor Napoleon invaded France, but was soon ousted by the Ottomans, with the help of the British. By 1805 a Turkish officer named Muhammad Ali, sent to Egypt by the Ottomans to drive out the French, quickly rose to power and attempted to modernize Egypt, improving agricultural techniques and promoting industrialization. Muhammad Ali eventually raised the ire of the English, who feared a strong independent power in the Mediterranean, and eventually Egypt was brought under British control, until they granted the colony independence in1936.

Medical practices of ancient Egypt

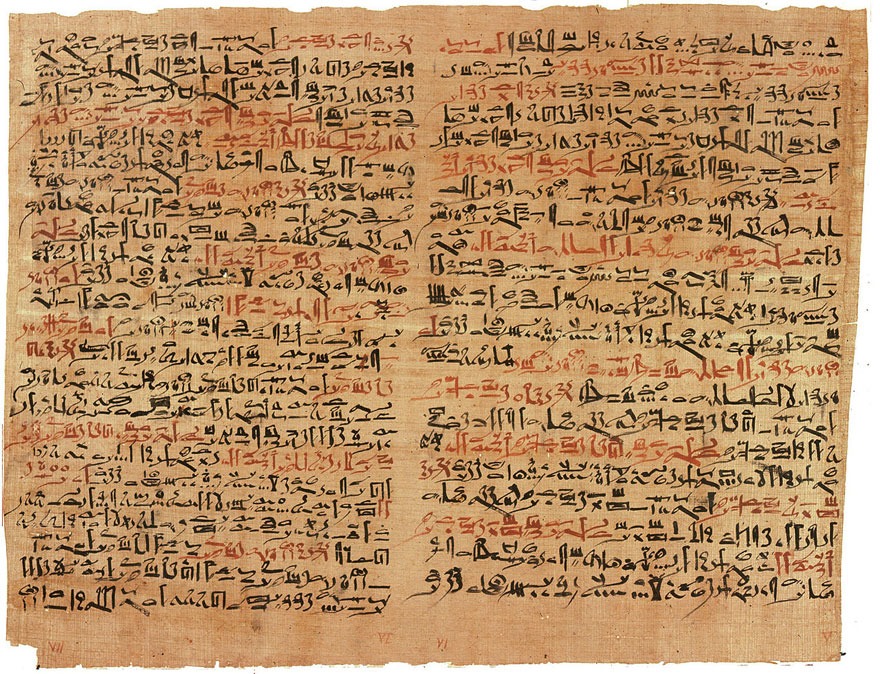

The medical practices of the ancient Egyptians appear very much similar in orientation to the practices of Mesopotamia, containing both shamanistic and medical aspects. Unlike the cuneiform clay tablets of Mesopotamia, what we know of ancient Egyptian medicine is contained within a few papyri, a durable parchment made from the pressed stems of Cyperus papyrus, a sedge that grows along the banks of the Nile. The oldest yet discovered medical papyrus is the Kahun Papyrus, dating back to 1825 B.C.E., composed during the reign of Amnemhat III. The most famous and descriptive papyri however are the “Edwin Smith Papyrus” (c. 1600 B.C.E.) and the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1500 B.C.E.), although the latter appears to make reference to the first Dynasty (c. 3000 B.C.E.), suggesting that its origins are much earlier (Arab 2001; Demand 1997).

The Kahun Papyrus was discovered by Flinders Petrie in April of 1889, and is divided into thirty-four paragraphs that describe methods for determining pregnancy and the sex of the fetus, and well as the diagnosis and treatment of several gynecological disorders. Among the more colorful methods for determining fertility described by the Kahun Papyrus was to place a clove of garlic in the vagina, and if the odor was detected on the breath then fertility was assured (Arab 2001). This of course would rule out some obstruction of the fallopian tubes. Sex determination was also described, achieved by attempting to germinate both wheat and barley with the urine of the pregnant mother (Arab 2001). If the mother was carrying a male it said that the wheat would germinate first; if barley were to germinate first, the fetus was considered to be a female. The Kahun Papyrus also provides techniques for female contraception, one recipe described in which a piece of cloth soaked in a mixture of honey, acacia gum (Acacia Senegal), crocodile dung and sour milk was introduced into the vagina (Arab 2001).

The Edwin Smith Papyrus, named after an American dealer of antiquities that purchased the papyrus in 1862, is a relatively short papyrus of about 5 meters in length, chiefly concerned with surgery, describing 48 surgical cases of wounds of the head, neck, shoulders, breast and chest. The text unfortunately appears to be incomplete, and ends rather abruptly in mid-sentence. The Edwin Smith Papyrus also lists the signs and symptoms for each condition, followed by treatment strategies (Arab 2001; Demand 1997)

The Ebers Papyrus is named after Egyptologist George Ebers, who purchased the papyrus from Edwin Smith in 1872. It is a very long roll of papyrus, about 20 meters in length, and is primarily a reference to internal medicine, as well as diseases of the eye, skin, extremities, gynecology, and some surgical techniques. The Ebers Papyrus also lists anatomical and physiological terminology, and provides an extensive section on treatment, in which 877 formulations and 400 individual drugs of vegetable, mineral and animal origin are described (Arab 2001; Demand 1997).

The practice of medicine in ancient Egypt appears to mirror that of Mesopotamia, with a clear division between magico-religious and medical practices. Physicians who practiced medicine were called sunu, while shamanistic healers were termed sau. Both types of physician were active participants in health care delivery and co-existed peacefully. Standing between these two practices were the priests of Sekhmet, a lioness-goddess who was worshiped in Memphis and could punish humanity for their sins by inflicting disease. Those inflicted by her wrath could appeal to the priests of Sekhmet to remove the condition (Arab 2001; Demand 1997).

Egypt maintained a network of medical training centers as early as the 1st dynasty (c. 3150 — 2925 B.C.E.), called peri-ankh or “houses of life.” The most reputable of these was that established by Imhotep in Memphis, the vizier of King Zoser (c. 2700 — 2625 B.C.E.) and builder of the stepped pyramid at Saqqara (Arab 2001). Imhotep was later worshipped as the god of healing, and was later identified with Aesclepius, the Greek god of healing. Women also played an important role in the delivery of health care, and not just as midwives. Amongst the more famous physicians of Egypt was Peseshet, a venerable female physician who practiced during the fourth Dynasty. She was given the title “Lady Overseer of the Lady Physicians,” and supervised a large contingent of qualified female physicians (Arab 2001; Demand 1997).

Egyptologists used to speculate that the great pyramids of Egypt were built by slaves under poor working conditions, but recent research has reversed these earlier conclusions. It appears that the paid laborers who built the pyramids had some form of health care, and were provided with medical insurance, such that a worker could obtain compensation from the temple to cover lost wages and cover medical expenses. The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484 — 425 B.C.E.) reports that ample amounts of radish, onion and garlic were supplied to the workers at mealtime (Arab 2001). These foods are known to contain natural immunomodulants that would have helped protect the workers against infection in the crowded work camps.

Ancient Greek medicine

Greek medicine is traditionally said to have begun with Asclepius, the son of the god Apollo and the virgin Coronis. Although the existence of Asclepius cannot be validated with any degree of certainty, some sources place his birth in Epidaurus (about 60 km southwest of Athens), in about 1250 B.C.E. There is a striking similarity between Asclepius and the Imhotep however, and it is likely that Asclepius was a cultural appropriation from Egypt. Nonetheless, a rich mythology surrounds Asclepius, beginning with the execution of his pregnant mother, Coronis, when Apollo learned that she had been unfaithful. Apollo, however, rescues Asclepius from the funeral pyre and puts him under the care of Chiron, a wise centaur who taught him the art and science of healing. Asclepius is represented carrying the caduceus, a staff with a serpent coiled around it, which has since been taken by the medical profession as its symbol. His daughter is Hygieia, the goddess of health, although some revisionists refer to him as his mother, just as prevention should logically precede medical treatment. Asclepius was later killed by Zeus, for using a draught given to him by Athena to raise the dead.

The earliest textual reference to the practice of medicine in ancient Greek culture comes to us from Homer, author of the two epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, from about the eight century B.C.E. Of these two works, the Iliad contains the majority of medical information, describing various war injuries with surprising detail and accuracy. Homer also describes the treatment of these injuries, through means of bandaging and herbal remedies. The son of Asclepius, Machaon, is mentioned by Homer as a physician and a warrior, whose injuries were treated with a cup of hot wine sprinkled with grated goat cheese and barley (Iliad XI. 638).

Hippocrates: the father of Unani medicine

Beyond its mythological origins, Greek medicine began in part with the rhizotomoki or root-collectors, wandering herbalists who plied their trade from town to town in much the same way as the modern hakim of Unani medicine. These practitioners later evolved into meticulous botanists, developing a coherent and rational understanding of botanical medicines that was exemplified by the work of Theophrastus and Dioscorides. The earliest schools of Greek medicine appear to be founded by Thales of Miletus (c 639 — 544 CBE) and Pythagoras of Samos (c. 580 — 489 B.C.E.), both of whom studied with Egyptians priests and physicians. But the most influential and highly regarded source of information on the practice of ancient Greek medicine comes to us from Hippocrates of Cos (c. 460 — 380 B.C.E.). He is thought to be a contemporary of Socrates and possibly a member of the Asclepiads, a guild of physicians that traced its origins to Asclepius, the god of healing. Hippocrates appears to have led a kind of rebellion against the existing medical practices of ancient Greece however, and set up a separate school of medicine on the island of Cos. It is generally believed that Hippocrates attempted to sublimate the magico-religious elements found in the Asclepiad, instead promoting a rational approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Nonetheless, the actual details of his life are shrouded in mystery, although tradition tells us that Hippocrates attained a substantial degree of notoriety during his lifetime. Over 60 medical treatises have been traditionally attributed to him, collectively referred to as the Hippocratic Corpus. In actual fact however, these texts were written over a 200-year period before, during and after the death of Hippocrates. Many of the texts contain contradictory information, which often confused the practice of medicine over the succeeding centuries. Although some 300-400 plant and mineral drugs have been enumerated in these works, Hippocrates did not specifically write a herbal, probably relying instead on the lists of medicaments compiled by Thales and Pythagoras.

The main thrust of Hippocratic medicine was rational inquiry, of understanding the mechanics behind illness, and the development of a complimentary therapy that reversed its progression and arrested its signs and symptoms (i.e. opposite cures opposite, allopathic therapy). This approach was in sharp contrast to the magico-religious healing practices of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, where it was the similarities between things (i.e. like cures like, homeopathic therapy) that often directed the cure.At the same time, Hippocratic medicine also emphasized the concept of mental, emotional, and physical balance, in much the same way as Ayurveda or Chinese medicine does. A disease was considered to represent an inequity among these components, and it was the physician’s job to harness the patient’s recuperative powers (the healing power of nature, vis medicatrix naturae in Latin, quwwat-e-mudabbira in Arabic) to restore balance. To achieve this, Hippocrates employed a humoral system to explain the basic dynamics of bodily function, comprised of the four cardinals of blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm. Tradition in Unani suggests that Hippocrates developed this theory after observing freshly-drawn blood: the red portion of blood being the blood humor, the white or clear material mixed with the blood being phlegm, the yellow-colored froth on top yellow being bile, and the heavy part that settles being black bile. Some researchers suggest that the humoral concept might have evolved from the ancient Greek theory of the elements (vis. Earth, Water, Wind and Fire), whereas others think that the Greek system was a modification of the much older Ayurvedic humoral system called tridosha. Although Hippocrates is often cited as the inspiration of modern medicine, Hippocrates was nonetheless an enthusiastic advocate of the holistic principle: “There is in the body no one beginning, but all parts are alike beginning and end; for a circle has no beginning” (Gruner 1970, 111).

Theophrastus and Dioscorides: the first botanists

Among the first and most important contributors to the ancient Greek knowledge of medicinal plants was Theophrastus (c. 327 — 285 B.C.E.), referred to as the Father of Botany. He wrote two books on botany, and describes over 500 plants in his Historia plantarum. The work of Theophrastus is marked by his emphasis upon observation and logical inferences, rather than the speculative or theoretical musings of his contemporaries. Though minor contributions were made in the succeeding years, the work of Theophrastus only further evolved with the scientific rigor of Pendanios Dioscorides in the first century B.C.E. Dioscorides was a Greek physician that traveled extensively with the Roman Army, treating injuries and collecting and classifying the medicinal plants that he found. In his great work, De Materia Medica, Dioscorides provides a name for each plant, including the Greek synonym, a botanical description, the habit in which it can be found, and its preparation, dosage and storage as a medicine. It appears to be a compilation of his own insights as well of the work of Hippocrates and Theophrastus, as well as other herbalists that went before.

The system of medicine that was developed by the Greeks over a 300 to 400-year period became enshrined in the Library of Alexandria, with students and scholars from all over the known world traveling there to study, teach and practice at the School of Medicine. At this point Greek medicine was a synthesis of the practices of the early rhizotomoki with Hippocratic and Egyptian medicine, as well as the new medical knowledge that had been obtained in the military campaigns of Alexander and the Roman Empire. It was here in the fertile land of the Nile Delta that Claudius Galen of Pergamus (c. 130 — 200 C.E.) came to study, his later work setting the standard for medical practice in European culture for well over a thousand years.

Claudius Galen: the patron physician

The son of an architect, Galen was introduced to medicine at an early age, traveling to Alexandria to learn study Hippocratic medicine. By about the age of 27, Galen had secured a reputation as a skilled physician, administering medicines to gladiators and learning much about surgery, dietetics, and exercise. In 161 or 162 C.E., Galen went to Rome, presenting lectures on anatomy and physiology and was soon was hired as the physician of the household of the Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius. This position enabled Galen to write, research, and travel, and by the end of his life he had written several hundred works on anatomy, physiology and therapeutics.

Galen was an enthusiastic adherent of Hippocratic medicine, and wrote extensive commentaries on the Hippocratic corpus and other herbals, indicating especially those parts or texts that he felt to be lacking or inauthentic. What stands out as his most complete work however is De Simplicibus, a massive text that categorized all known medicinal plants according to their effect on the humoral system. The effect that each plant had on the humors was measured on a scale of degrees. Thus a plant drug that was determined to have a cold and wet energy, thereby acting to aggravate a phlegmatic tendency, would be graded cold and wet to the first, second or third degree, the first degree having the strongest activity. It is a tribute to Galen’s genius that no herbalist ever attempted to replicate or refine his work, and this text and others written by Galen became among the most important medical texts in Europe for centuries.

Galen facilitated an important shift in medical thinking, away from the naturalist, earth-centered approach of the folkloric traditions, to a complex and highly specific set of rules based upon an unchanging theoretical structure. Reflecting the complexity of their thinking, Galen and his contemporaries increasingly relied upon complex poly-herbal formulae, instead of the local herbal remedies that were easily obtained and simply prepared. Perhaps the best example of this is the Galene Theriac, Galen’s revision of an earlier formula, that he prescribed to treat all manner of illness and later came to be thought of as a kind of panacea. To make such a formula however, Galen started with the best Falernian wine from the Campania district in Italy, and the sweetest honey from the Hymettus mountains in Greece, commingled with a varied list of ingredients that included pieces of viper flesh, bitumen from Judea (Israel), opium from Asia Minor (Turkey), and crocus from Cililia (Armenia) (Griggs 1981, 17). All this was mixed and pounded together for at least forty days, and then aged for no less than twelve years before it had reached its prime. Even at this early juncture, the theory and practice of herbal medicine was out of reach for the common people.

If Galen had been born earlier, his contribution to medicine might not been so monumental, but in the century that followed his death the Roman Empire underwent a serious period of decline. In the ensuing break-up of the Holy Roman Empire, with the Visigoths breathing down the neck of Rome, innovation and study took a back seat to Christian doctrine, and for better or worse, the work of Galen became rigidly enshrined as the ultimate medical authority of the Church.

Islamic medicine

Islamic medicine proper, or that which we can say is derived solely from the Arabian Peninsula and whose practices have only in latter centuries reflected the now dominant aesthetic of Islam, is probably best reflected in the shamanistic practices of the Bedouin peoples. These ancient tribal peoples of Arabia, as well as neighboring Syria and parts of northern Africa, have proven to be a treasure-trove of knowledge for ethnobotanists and theologians interested in the uses of many of the plants mentioned in the bible. The Bedouins are even mentioned in the Old Testament as the children of Shem, son of Noah (Sajdi 1996). The Bedouin people have maintained a continuous way of living from a time well beyond that of recorded history, reflecting very closely the common practices of the Paleolithic peoples that inhabited the Mid East some 30,000 years ago. Their distinct hunter-gatherer, typically nomadic lifestyle has resulted in pervasive tribal customs that survived the rise and fall of the larger agricultural-based societies, such as Mesopotamia.

Unlike modern Unani medicine however, Bedouin medicine is essentially shamanistic, lacking the rational empiricism of the Greeks or the theoretical machinations of Galen, more akin to the sympathetic and magical practices of Egyptian and Mesopotamian medicine. The central figure in Bedouin shamanism is the fugara, a member of the tribe that teaches, tends the sick, and provides spiritual advice (Sajdi 1996). The term fugara actually means “weak,” referring to the practice of all fugaras of limiting how much food they eat, as well as their habit of fasting on a regular basis. Thus a fugara typically looks skinny, and may appear weak, but according to Bedouin belief, has the ability to find stolen souls and locate hidden objects, entering into the unseen world of the spirits, speaking the secret language of the tribe as its mythology (Sajdi 1996). A Bedouin shaman may also use the language of the Qur’an, specifically, certain passages and phrases in the Qur’an that speak of Allah’s attributes, in complex healing ceremonies. These prayers are sometimes written on a piece of paper, leather or bone, placed in a glass of water and drunk by the patient, buried in the ground, or carried by the patient as a talisman (Sajdi 1996). These prayers may also be given to the patient to recite aloud or as an object of meditation.

Central to the practices of the fugara are techniques such as chanting, drumming, manipulation of the breath, and fasting, as well as the use of psychoactive entheogens to assist their entrance into the spiritual realms (Sajdi 1996). One commonly used plant among the fugara is Harmla (Peganum harmala, Zygophyllaceae; Syrian Rue), which contains indole alkaloids such as harmine, similar to but more potent than Passionflower (Passiflora incarnata), having hypotensive and depressant activities upon central nervous function. It is a common ingredient in many of the simple herbal combinations used by the Bedouins, and when burned with incense, is used to cure patients possessed by a djinn, or evil spirit (Sajdi 1996).

According to Bedouin mythology, the Harmla plant was originally a woman, a jealous wife who accused her husband’s sister of infidelity, tricking her husband to kill her to save the family’s honor. After the nature spirits had protected the virtuous young woman from death, the brother discovered his wife’s treachery and cut off her head, crying aloud that her head should become a bush so repulsive a donkey wouldn’t eat it. The head was then transformed into the Harmal plant, with its dark bitter seeds (Sajdi 1996). The perspective presented by this story of Harmla reflects a belief among the Bedouin shamans that plants could house nature spirits or specific spiritual qualities that could neutralize the negative effect of evil spirits, the foremost cause of disease. The Bedouin shamans also make use of minerals, gemstones and amulets in the same fashion.

While Bedouin practices reflect the rich storehouse of Arabic tribal knowledge, their naturalist and pagan influenced practices are at odds with Islamic theology. Nevertheless, many of the cultured Arabic sages, learned in the ancient books of Greece and Egypt, retained a distinct admiration for the nomadic Bedouin people, reflected in the comments of the great Arab philosopher, Ibn Khaldûn (c. 1332-1406 C.E.), in his Muqaddimah:

“As compared with those of sedentary people, their (i.e. the Bedouins) evil ways and blameworthy qualities are much less numerous. They are closer to the first natural state and more remote from the evil habits that have been impressed upon the souls (of sedentary people) through numerous and ugly, blame-worthy customs. Thus, they can more easily be cured than sedentary people. This is obvious. It will later on become clear that sedentary life constitutes the last stage of civilization and the point where it begins to decay. It also constitutes the last stage of evil and of remoteness from goodness. Clearly, the Bedouins are closer to being good than sedentary people.”

Rise of Islamic Unani medicine

By about 400 C.E. the last vestiges of the Roman Empire in Europe had finally collapsed, and with it, general access to the accumulated knowledge of Greek and Roman civilization. What little remained was the preserve of the Church, bound up with Christian dogma and generally inaccessible to an illiterate populace. Artistic and technical skills were lost, and medicine became reliant upon simple folk remedies and superstitions. It was in the East however, that the Byzantines, Syrians and Arabs made sure that this treasure-trove of knowledge remained preserved.

For nearly four centuries the School of Medicine in Alexandria, Egypt, continued to replenish the eastern Mediterranean with a supply of skilled physicians and botanists. With the decline of Alexandria a new school in Antioch, Syria, picked up the slack, and gradually the work of Graeco-Roman scholars were translated into Syriac, the language of the Syrian Christians. By the fifth century C.E. Arabic-speaking Christians were busily translating these works in their own language.

Then, early in the seventh century C.E., a man named Muhammad arose out of the desert of southwestern Arabia, bringing together several lawless Bedouin tribes under the realization that “there is no God, but Allah.” Muhammad taught that every person was equal in the eyes of Allah, and that each should make islam (submission) to Allah. In this vein, Muhammad promoted the dismantling of the class-based tribal system, and preached against the injustices of poverty and misogyny (as witnessed by his support of a woman’s right to a divorce and the prohibition of the common practice of female infanticide). Although his reformist message attracted a great deal of support, soon after of Muhammad began to share his spiritual messages, he also had many detractors that sought to preserve the status quo. About 12 years after he began to preach in the city of Mecca, Muhammad had to flee to Medina in 622 C.E., where he regrouped with supporters. Eight years later in 630 C.E. Muhammad’s supporters committed themselves to the jihad, or holy war, to rid Mecca of its “decadent” pagan influence. Once he had taken the city, Muhammad ensured the destruction of all the idols in the Kaaba, the most sacred shrine of the city, and this place became the first mosque (house of worship) in Islam. With his success at Mecca, Mohammad continued the jihad, bringing the entire Arabian Peninsula under the yoke of Islam.

With the death of Muhammad in 632 C.E., Abu Bakr was elected caliph, the leader of the Muslim world. After Mohammad’s death a few tribes revolted but Abu Bakr subdued and restored them to Islam. Following Abu Bakr were a series of successful caliphates that continued the jihad, gobbling up the decaying Persian Sassanid and much of Christian Byzantine empires. With the establishment of the Ummayad caliphate in Damascus in 661 C.E., the jihad was expanded further, and Arabic culture underwent a rapid period of development. First the Ummayads added Turkey, and then followed this with expeditions into India and China. In 711 C.E. the Ummayads invaded Spain, making their way into the Pyrenees Mountains until their armies were stopped by Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours, in 732 C.E.. In 750 C.E. two branches of Mohammad’s family, the Abbasids and Alids, overthrew the Ummayads, the young Ummayad prince escaping to Spain and establishing a separate caliphate in Cordova, Spain in 756 C.E.. Left to battle over the eastern portion of the former Ummayad Empire, the Abbasids eventually outwitted the Alids and established the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, and control over much of West Asia and northern Africa.

The relatively rapid rise of Muslim empire, which from Mohammad’s victory in Mecca to the establishment of the Ummayad invasion of Spain was less than a hundred years, suddenly exposed the Arabs to the vast storehouse of Graeco-Roman knowledge. Perhaps embarrassed when they compared the refined aesthetic of the Persian and Byzantine empires to their own tribal customs, the Abbasid leaders pursued a lifestyle never before imagined by their Bedouin forebears. In 813 C.E. the Abbasid caliph Al Mamum Ar Rashid is reported to have had a vision of Aristotle, who told him that reason and revelation were mutually dependent entities (Nagamia 1995). Inspired thus, Al Mamum petitioned the rather weak Byzantine king Michael I for access to the texts of ancient Greek and Roman knowledge, apparently neglected and stored in a dilapidated building (Nagamia 1995). Many of these works, including those of Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides, were taken back to the Bayet al-Hikma (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad, built a few years earlier by Harun Al Rashid (c. 786-809 C.E.). Here the Arabs busily translated these texts into Arabic, and soon Baghdad became a world center for learning, with the caliphate actively encouraging scholars from as far as India to come and share their knowledge. Under the Abbasid dynasty Arabic culture blossomed, feeding off the centuries of Graeco-Roman knowledge. In the succeeding two centuries following the Abbasids, under the influence of the Seljuk Turks (c. 9 — 11th century C.E.), Unani medicine was at its height, influencing and guiding health care for much of the Mid East and Europe. Some researchers have even uncovered evidence of the presence of a Unani school of medicine in Beijing, China, in the 11th century C.E., perhaps influencing the development of Chinese pulse diagnosis.

Islam is built upon the foundations of the Judeo-Christian tradition, and all teachings and prophets from these traditions are recognized by the Muslim faith. According to Muslims, Muhammad was simply that last and greatest of the prophets sent by God to inspire humanity. The Muslim faith teaches that Allah provides all medicaments necessary to heal the ills of humanity, and that these occur in the natural environment. To this end Muslims have relied upon the Qur’an, but also the Hadith, a secondary text that contains sayings of Muhammad, to guide their approach to health care. While the Qur’an mentions the benefits of consuming certain foods such as honey and the abstinence of alcohol, it contains very little specific information on health and disease, unlike the Hadith which details guidelines on diet and the treatment of simple ailments like sore throat, conjunctivitis and fever (Nagamia 1995).

The belief by Muslims that Allah provides all that is needed encouraged a renewed interest in medicinal plants, and using Dioscorides as a model, the Arabs added hundreds of medicinal plants to their materia medica. The Arab leadership also oversaw the construction of many teaching hospitals, where it was clinical and empirical medicine rather than pedantic discussions of theory that prevailed. Unani medicine nonetheless retained magico-religious elements in medical practice, using upon astrology to portend the duration and success of a particular treatment, as well as the usage of charms and amulets typified in Bedouin practices.

Although the rise of Unani medicine is certainly linked to the Abbasid efforts in Baghdad, the Arabs were also the fortunate inheritors of the school of medicine at Jundishapur, formerly located in western Iran, near the city of Ahwaz. The city of Jundishapur was established by the Persian Sassanid emperor Shapur I (c. 241-272 C.E.) as a settlement for Greek prisoners (Nagamia 1995). Within a few years however Jundishapur had grown very quickly, attracting Greek-Syriac scholars from Antioch who helped establish Jundishapur’s reputation as a center of learning (Nagamia 1995). During the reign of Khusraw Anushirwan (c. 531-579 C.E.) a university and Hippocratic school of medicine were established, modeled on those at Alexandria and Antioch (Nagamia 1995). The city later benefited when the Nestorians chose Jundishapur as a refuge from the rule of Emperor Zeno, who after the conflict over iconoclasm and the divinity of Jesus, had closed of the Nestorian School at Edessa. With the coming of the Nestorians, who had followers as far away as India, Jundishapur began to attract Sanskrit scholars and physicians, and under the direction of Burzuyah, the physician-vizier of Khusraw Anushirwan, several Indian medical texts were translated into Syriac (Nagamia 1995). When the Arabs invaded Jundishapur during the caliphate of Hadrat Umar (c. 634-644 C.E.), the city continued to flourish under their rule. During the later Abbasid dynasty the Christian physician Jirjis Bukhtyishu (lit. “Jesus has saved) of Jundishapur was invited to Baghdad to treat the ailing Caliph Al Mansur (Nagamia 1995). After successfully treating the Caliph, Jirjis Bukhtyishu’s son later settled in Baghdad to build its first hospital, heralding the migration of an increasing number of physicians and scholars from Jundishapur, which only added to Baghdad’s prestige as the new Alexandria (Nagamia 1995).

al Razi: the clinician

Initially it was the Hippocratic school of medicine in Jundishapur that inspired the early Muslim physicians, with an emphasis upon rational inquiry, and preventative regimens such as diet and exercise. Perhaps no other Islamic physician best exemplified this approach than Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya’ al-Razi (c. 865 — 925 C.E.), who stated “where a cure can be obtained by diet, use no drugs and avoid complex remedies where simple ones will suffice.” Al Razi, later known to the European world as “Rhazes,” was a brilliant clinician, musician, philosopher, and alchemist. One story recounts that al Razi determined the location for a hospital in Baghdad after setting out raw meat in four different quarters of the city. The meat located in the quarter of the city that had undergone the smallest degree of putrefaction was then chosen as the location for the new hospital (Nagamia 1995; Savage-Smith 1994).

Among his many contributions to medical science, the Kitab al-Hawi fi al-tibb (Comprehensive Book on Medicine) has been revered by physicians for centuries, both in the Muslim world and in Europe. It was a large, informal notebook in which he placed extracts from earlier Graeco-Roman authors regarding disease and therapeutics, juxtaposed with his own clinical experiences. After his death the Hawi, or Comprehensive Book, was purchased from al Razi’s sister by Ibn al Amid, the vizier to the Persian ruler Rukn al Dawlah in 939 C.E. (Savage-Smith 1994). Ibn al Amid supervised the organization of this text by al Razi’s pupils and the text became available to all practicing clinicians. The Hawi remains an important source of Graeco-Roman and early Arabic medical knowledge, much of which is now lost (Savage-Smith 1994).

Al Razi appears to have been a pragmatic physician, emphasizing his interest in therapeutics as opposed to theory and the classification of symptoms. He certainly relied upon the work of Galen, but was not so in awe of him that he wouldn’t correct what he perceived to be errors (Savage-Smith 1994). For example, al Razi said that the many cases of fever he observed in the hospitals of Baghdad did not conform to Galen’s description. Al Razi maintained a flexible and inspired approach to healing, but was not interested in altering the theoretical foundations of Hippocrates or Galen.

Ibn Sina: the Persian Galen

The pragmatic and flexible emphasis of al Razi however, was eventually superceded by the intellectual rigor of Abu `Ali al Husayn ibn `Abd Allah ibn Sina, or more simply, Ibn Sina (aka. Avicenna, c. 980 — 1037 C.E.), considered by many to be the greatest of the Islamic scientists. Ibn Sina was born in 980 C.E. in a village near Bukhara, which today is located in Uzbekistan. Ibn Sina demonstrated his genius at an early age, memorizing the holy Qur’an by the age of 10, and beginning his studies in medicine when he was only 17, pronouncing that the subject was, in his own words, “not difficult” (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994). By the age of 18 Ibn Sina had built up a reputation as an excellent physician and was summoned to attend the local ruler Nuh ibn Mansur (c. 976-997 C.E.) (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994). In gratitude for his services Nuh ibn Mansur allowed Ibn Sina to have access to the royal library, which contained many rare and unique books. Ibn Sina threw himself into the study of these texts, and by the age of 21 was a highly respected man of learning (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994).

In the succeeding years Ibn Sina became renown for his book learning and medical prowess, and was much sought after as he travelled all over Turkestan, teaching and practicing medicine. Eventually he ended up in the service of the Amir (king) Shamsud-Dawala of Hamadan as prime minister, after he had successfully treated the grateful Amir for colic (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994). Ibn Sina led a strenuous life, performing his duties as prime minister during the day, and attending to his studies and teaching at night. To friends that were concerned for him and suggested he slow down, Ibn Sina said “I prefer a short life with width to a narrow one with length” (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994). After the death of the Amir, Ibn Sina fled to Isfahan, and after escaping a few brushes with the law and some time in prison, was employed in the service of the ruler of the city, Ala al Daula, whom he advised on scientific, military and literary matters. Ibn Sina died in 1037 in Isfahan at the age of 58, and was later buried in Hamadan (in modern-day Iran), where his grave can be seen today.

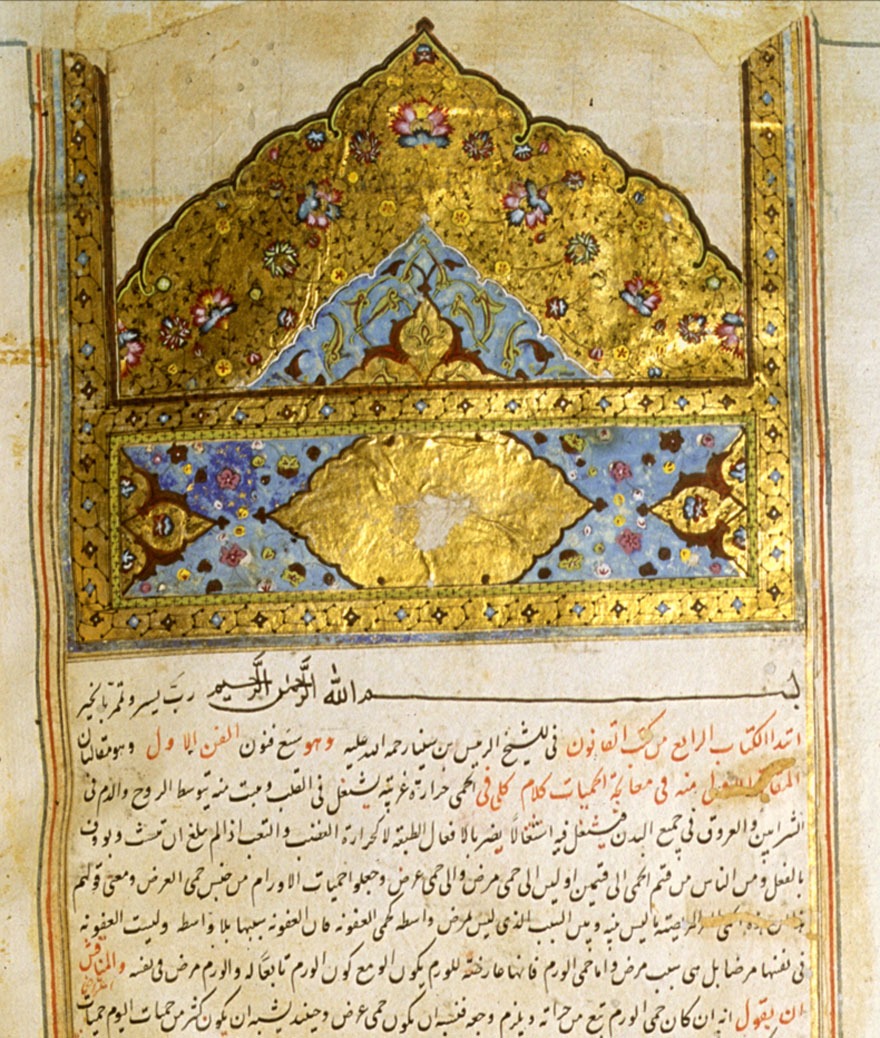

Beyond his consummate devotion to his work and his genius for retaining information, Ibn Sina shared with Galen a passion for order, to arrange facts and phenomena into a coherent system of knowledge. Among his scientific works, the most important are the Kitab al Shifa (Book of Healing), a philosophical encyclopedia based upon Aristotelian philosophy, and the million-word al Qanun al Tibb (Canon of Medicine), representing the “final codification of Greco-Arabian” concepts on medicine. The Qanun is divided into five books, the first dealing with general principles of medicine; the second with simple plant drugs arranged in alphabetical order; the third with diseases of particular organs and tissues of the body; the fourth with local diseases that spread to other parts of the body, such as fever; and the fifth with complex formulae (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994). Ibn Sina demonstrates his many clinical insights in the Qanun, detailing for example the contagious nature of tuberculosis and its spread by soil and water. He provides a differential diagnosis of ancylostomiasis (hookworm disease) and attributes the condition to an intestinal worm (Monzur 1990; Savage-Smith 1994). The Qanun’s materia medica details some 760 drugs, commenting on their usage and efficacy. In this text, Ibn Sina was also among the first to recommend the testing of a new drug on animals and humans before their widespread usage. To his contemporaries, Ibn Sina’s al-Qanun was the perfection of medicine, displaying an almost mathematical accuracy that ensured its unrivaled status as the most important text of Unani medicine. But lest we content ourselves by defining Ibn Sina as a man of medicine, we should not forget his authority on a wide variety of subjects including philosophy, theology, geometry, and astrology, for which he is still revered by Muslims to this day.

Arab Pharmacy

Beyond the scintillating brilliance of al Razi, Ibn Sina and the other philosopher-physicians of the Islamic world, the Arabs perhaps made their greatest contribution to the field of medicine in the area of pharmacy. The first apothecaries of the Arab world began to appear in Baghdad during the eighth and ninth centuries, containing a dizzying array of medicinal plants from the mid-East, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Barbara Griggs theorizes that this eclecticism of the Arab pharmacists was due, in part, to the harsh and forbidding nature of the Arab homeland, the deserts of which could provide comparatively few medicines (1981, 29). But whether it was for this reason, or simply their expanded awareness of the possibilities in herbal medicine, the Arab pharmacists are responsible for the many exotic herbs such as Clove (Eugenia caryophyllus), Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), Black Pepper (Piper nigrum), and Saffron (Crocus sativus) that were eventually introduced into European usage. The Arabs refined the usage of purgatives such as Senna pods (Cassia acutifolia), so important to remove the excess humors, by adding aromatic herbs to reduce their emetic and griping properties. Arab herbalists also introduced many drugs of animal and mineral origin into general practice, such as deer antler, earthworms, scorpions, rhinoceros horn, and the highly valued bezoar stone, found as a concretion in the digestive tracts of the wild Persian goat (Griggs 1981, 25-29).

Although he took his lead from Hippocrates and Galen, the Arab pharmacist made huge advances over Greek and Roman pharmacy in the preparation and processing of drugs. The Arab pharmacist utilized a vast array of equipment, “from vessels such as alembics (the head of a distilling device), cucurbits (the lower part of the distilling apparatus), receiving vessels, funnels, water-baths, filters, and crucibles, to the mortars and pestles needed to pulverize and crush substances, and the braziers and stoves needed to heat them” (Savage-Smith 1994). Among the more important techniques improved upon and introduced into pharmacy by the Arabs was distillation, with the invention of the refrigerated coil traditionally credited to Ibn Sina. The Arabs pharmacists used this invention to distill ethyl alcohol from fermented sugar cane, providing a new solvent for the extraction of plant constituents such as essential oils and the manufacture of tinctures. Tinctures have since become an important part of the therapeutic arsenal for modern clinical herbalists. Among their other contributions to pharmacy are volatile oil extraction and perfumery (Griggs 1981 25-29)

Unani medicine on the sub-continent of India

After his decisive defeat of the Persian king Darius in 330 B.C.E., Alexander the Great made his way through northern Afghanistan, waging a fierce military campaign against the small tribal kingdoms along his way to the sub-continent of India. In 326 B.C.E. Alexander and his Army descended down into the Kabul valley and crossed the great Indus river. When Alexander reached the city of Taksashila, King Ambhi peacefully surrendered to him, hoping to enlist his help against Ambhi’s fearful enemy King Paurava (aka. Porus), to the south. Most traditional European sources indicate that while the Punjabi king put up a brave battle against Alexander, the Greeks eventually won by out-maneuvering their cavalry against Paurava’s army of mounted elephants. Older Greek and Roman sources however dispute this version, indicating that Alexander was soundly defeated by Paurava, and faced a revolt among his own soldiers if he continued the battle. In any event, Paurava remained in control of the Punjab after the battle, and Alexander fought his way down the Indus valley until he reached its mouth, the army returning by sea and land to Mesopotamia. Alexander died in 323 B.C.E., having failed to extend the Macedonian Empire beyond the Indus River, concluding with some sadness that he had “nothing left to conquer.” Fortunately for him there is little mention of his name in the bulk of the ancient literature of India. And although Alexander’s impact upon India was minimal, his successors maintained commercial and cultural links, with many new medicinal plants introduced into the others’ materia medica.

The Hellenistic influence upon the culture of northwestern India is undeniable, perhaps exemplified best by the distinctly Grecian influence on the Buddhist sculpture of northwestern India (i.e. the Gandhara school). Similarly, the physicians and philosophers that accompanied Alexander appear to have shared their knowledge with local healers, and in so doing, Greek medicine found a fragile existence far removed from the Mediterranean. Some hakims in Pakistan to this day claim ancestry to the Greek physicians that accompanied Alexander, which is not so difficult to believe when one sees the shocks of curly red hair and blue eyes that can be found amongst the otherwise dark hair and brown eyes of the Indo-Arabic peoples of modern-day Pakistan.

With the rise of the caliphate in Arabia and the gradual Muslim advance into India, Greek medicine was reintroduced to the people of the sub-continent of India. By the early eighth century C.E. the Arabs controlled the Sind (Indus) region of modern day Pakistan, using it as a base to conduct raids into the lands of their eastern neighbors. But it wasn’t until Mahmud of Ghazni began a series of 17 raids from Afghanistan in the 11th century C.E. did India really begin to feel the impact of Muslim advance. The plundering and destruction of Mahmud’s forces seriously destabilized northern India society, the Hindu kings failing to co-operate with each other to stave off the Muslim conquerors. In the succeeding centuries Muslim forces continued to make gains in India, culminating in the establishment of the Mughal Empire in 1526 C.E. Under the patronage of the benevolent Mughal emperors, Babur, Akbar and Shah Jahan, Indian culture underwent an Islamic-inspired renaissance, exemplified by the Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan’s meditative memorial to his departed beloved wife. Unani medicine enjoyed an exalted status in India, with hospitals built throughout northern India, especially in Mughal centers Delhi and Hyderabad.

Between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries C.E. the Mongol and Turkish hoards conducted a series of raids on the Arabian caliphate in Baghdad, and on the Persian centers of learning such as Tabriz and Shiraz. With these invasions the flowers of Islamic culture withered, forcing many Unani physicians to flee to the subcontinent of India and Pakistan. These events were followed by the subsequent rule of the increasingly Euro-orientated Ottoman Empire, and as a result Unani centers of learning all but disappeared in the Arab world. Unani continued to develop in India however, especially under the patronage of the Mughal emperors. Among the many notable Indian Unani physicians was hakim Ali Gilani, who fled from Iran to India during the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar (c. 1556-1605 C.E.). Hakim Gilani became Akbar’s personal physician, writing an extensive commentary on Ibn Sina’s Al Qanun, earning him the title jalinoos e zaman, or, “Galen of the Age” (Ahmad and Qadeer, 18). Under subsequent British rule, which began by the mid 18th century, both Unani and Ayurvedic medicine were systematically undermined, and at one time the practice of either of these systems of medicine were punishable by death. Deprived of a beneficent patron, both Ayurveda and Unani struggled for many years until the British eventually relaxed their grip on Indian culture. Among the important centers of Unani learning that survived British rule were the Sharief family in Delhi, the Azizi family in Lucknow, and the Nizam family of Hyderabad (Ahmad and Qadeer, 18). In more recent times, there have been several notable individuals that shouldered the cause of Unani medicine, including Hakim Amjal Khan (c. 1864-1926 C.E.), who founded the Unani-Tibbia college in Delhi. Today, as an independent nation that is working to protect its heritage against the tide of western culture, India remains the world center for Unani medicine, supported and regulated by the central government (Indian Medicine Central Council Act, 1970).